Within a few years, wings—once controversial—became unavoidable across motorsport. What had seemed strange quickly became inevitable.

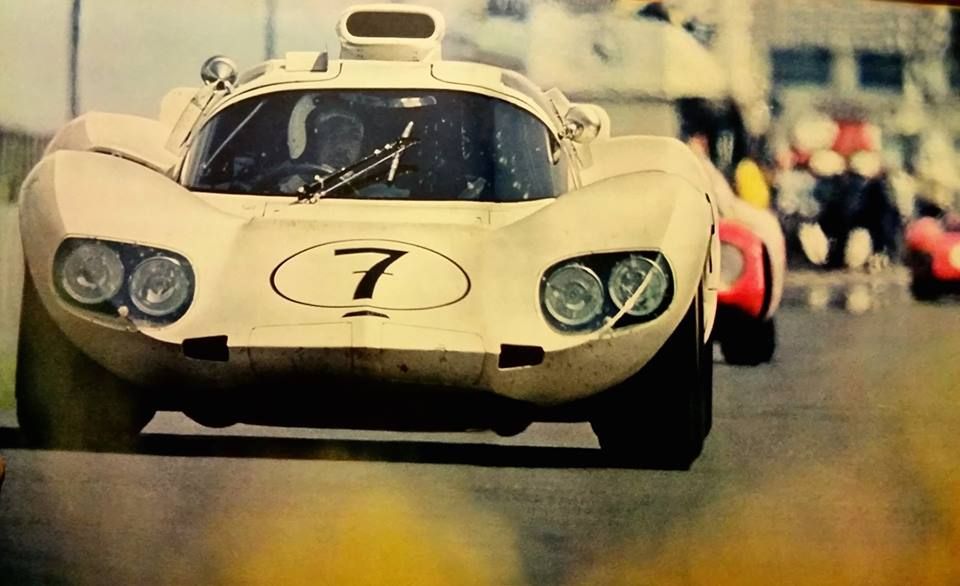

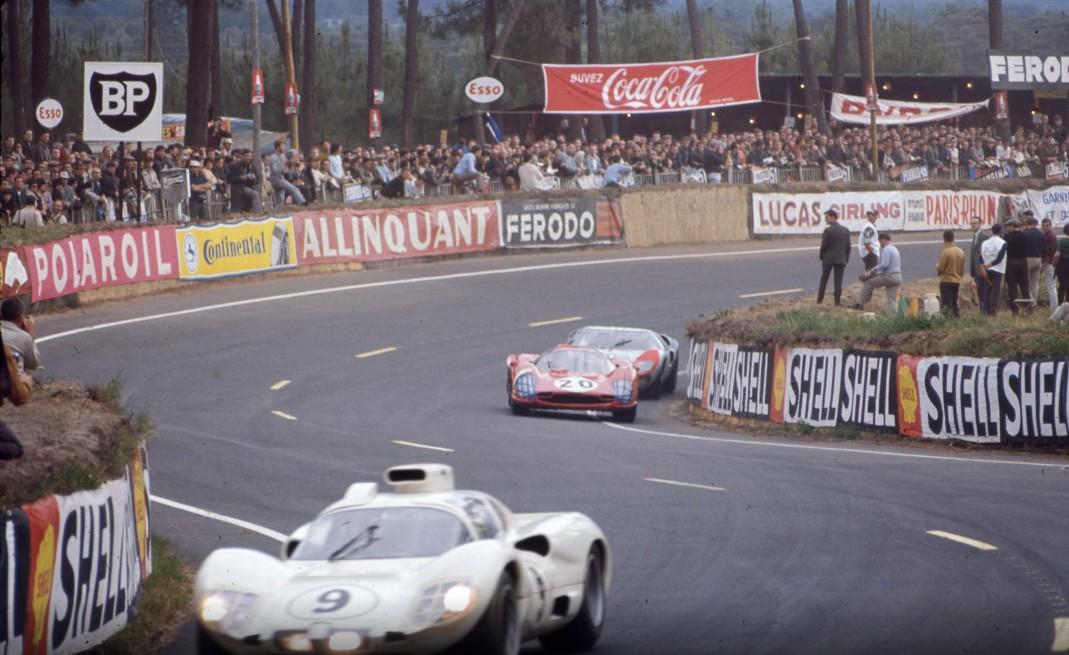

The Chaparral 2D did not arrive quietly. It appeared like a question aimed directly at racing orthodoxy: what if the car did not merely cut through air, but negotiated with it? In 1966, while most sports-prototypes still treated aerodynamics as a byproduct of shape, Jim Hall and his small, intensely focused team in Midland, Texas treated it as the central argument. The result was not just a faster car, but a different philosophy of control.

.jpg)

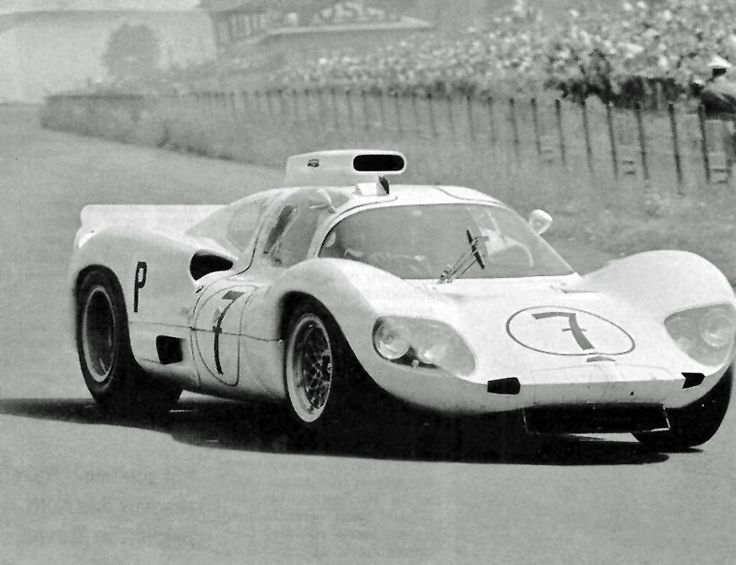

Jim Hall was not loud about his ambitions. Trained as an engineer, and thoughtful to the point of restraint, he approached racing as an experimental laboratory rather than a gladiatorial arena. The 2D followed earlier Chaparrals, but it marked a turning point: the first closed-cockpit Chaparral, and the first to fully commit to high-mounted aerodynamic devices as an integrated system rather than an afterthought.

The most striking feature, of course, was the rear wing. Elevated above the bodywork, mounted rigidly, and operating in relatively clean airflow, it was designed to generate downforce independently of body shape. This was a radical idea at the time. Rivals worried about drag; Hall worried about authority. The 2D was built to press its tires into the surface so the driver could ask more of the car without crossing into chaos.

The chassis and body were equally unconventional. Fiberglass construction allowed shapes that metal discouraged, and the enclosed cockpit reduced drag while improving stability at speed. Cooling, airflow management, and structural rigidity were treated as one continuous problem rather than separate departments. Nothing felt decorative. Every surface had a reason.

On track, the 2D demanded a recalibration of expectations. Drivers found a car that rewarded precision and punished vagueness. It was not theatrical; it was analytical. When it worked, it looked almost effortless, cornering flatter and faster than contemporaries that relied on mechanical grip alone. When it failed, it did so publicly, because innovation always carries risk.

Yet its true legacy lies beyond lap times. The Chaparral 2D helped legitimize aerodynamics as a controllable, engineerable force in racing. Within a few years, wings—once controversial—became unavoidable across motorsport. What had seemed strange quickly became inevitable.

The 2D stands today not as a relic of excess, but as a calm declaration of intent: racing could be smarter, cleaner, and more intellectually rigorous. It was not about domination. It was about understanding.

.jpg)

-