America’s first true sports car: flawed, loud, and brave, it transformed fiberglass dreams, national confidence, and Detroit’s idea of performance forever.

In the early 1950s, America had money, confidence, and absolutely no idea how to build a proper sports car. Europe, meanwhile, was producing things like Jaguars, MGs, and Ferraris—light, elegant machines driven by men who wore scarves and looked like they understood wine. America responded with chrome, V8s, and sofas on wheels.

Into this cultural mismatch stepped Harley Earl, General Motors’ high priest of style. Earl wasn’t an engineer. He was a showman. He believed cars should first seduce, then function. Performance was optional; drama was mandatory.

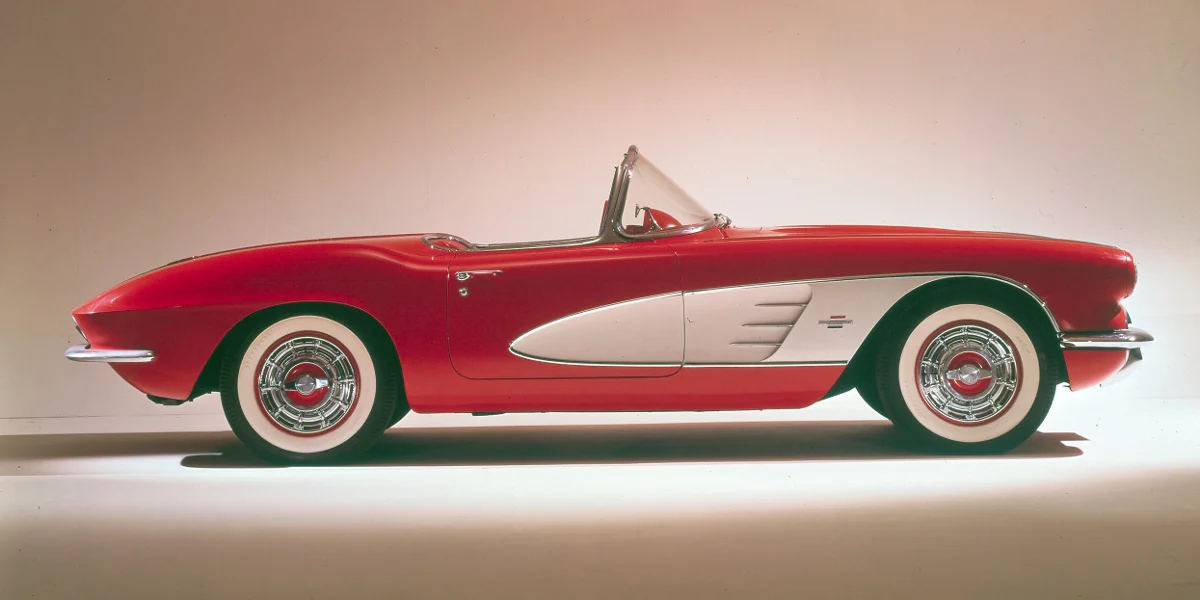

And so, in 1953, GM unveiled something borderline insane at the Motorama show: a low, sleek, two-seat roadster with no door handles, a fiberglass body (because steel was expensive and GM was feeling experimental), and the audacity to call itself a sports car. This thing would later be known as the Chevrolet Corvette C1.

At the time, it was about as American as putting ketchup on pasta—and yet, the crowd went feral.

The C1 wasn’t born in a wind tunnel. It was born in a styling studio fueled by cigarettes, sketchpads, and unchecked confidence.

The long hood, short deck proportions were deliberate—an attempt to visually punch Europe square in the jaw. The toothy grille, the flowing fenders, the wraparound windscreen: none of it was subtle. This was not a car whispering sophistication. This was a car yelling, “LOOK AT ME, I AM FAST,” even when it wasn’t.

And at launch, it really wasn’t.

Under the hood sat a 235 cubic-inch inline-six producing a thoroughly polite 150 horsepower, paired exclusively with a two-speed automatic. A two-speed automatic. In a sports car. That’s like putting training wheels on a fighter jet.

Sales reflected reality. In its first year, Chevrolet struggled to sell even 300 units. GM executives began quietly sharpening knives.

Enter Zora Arkus-Duntov—a Russian-born engineer, racer, and absolute menace to mediocrity.

Duntov saw the Corvette and immediately understood the problem: it looked heroic but drove like a float in a parade. So he did what all great car legends do—he annoyed management until they listened.

By 1955, the inline-six was gone, replaced by a small-block V8. This single decision transformed the Corvette from an attractive failure into a cultural weapon. Suddenly, it sounded right. It moved right. It felt American.

Duntov didn’t just improve the car; he gave it a mission. Racing. Speed records. Proving grounds. The Corvette stopped being a styling exercise and became a statement.

Let’s pause and talk about fiberglass, because this is where the Corvette quietly rewrote automotive manufacturing history.

At the time, using fiberglass for a production car body was lunacy. It was inconsistent, labor-intensive, and terrified quality-control departments. But it also allowed shapes steel simply couldn’t—tight curves, dramatic contours, and a lightness unheard of in Detroit iron.

The C1 wasn’t perfect. Panel gaps were… aspirational. Build quality was best described as “handmade in the loosest sense.” But it looked exotic. People didn’t care how it was built. They cared how it made them feel.

And that feeling sold dreams.

Early critics were brutal. European journalists laughed. Americans were confused. Sports car purists scoffed at the automatic transmission and soft suspension.

But here’s the thing: people noticed it.

Movie stars wanted one. Returning WWII pilots wanted one. Teenagers taped posters of it to their walls. The Corvette became less about lap times and more about identity. It said something about who you thought you were—or who you desperately wanted to be.

By the late 1950s, sales surged. Chevrolet leaned in hard, offering fuel injection, manual gearboxes, hotter cams. The Corvette was growing up, learning to throw punches.

The late C1 years—especially 1958 to 1962—are where things got deliciously ridiculous.

Quad headlights. Heavy chrome. Trunk “spears.” Styling flourishes layered upon styling flourishes. This was Harley Earl’s final, unapologetic indulgence before the cleaner lines of the 1960s took over.

And yet, despite all the ornamentation, the fundamentals were improving. More power. Better brakes. A chassis that could finally keep up with the engine. The Corvette was no longer pretending to be a sports car. It had become one.

Here’s the brutal truth: if the Corvette had been a European car, it would have died quietly after two years.

But America doesn’t kill its dreams easily.

The Corvette became a rolling experiment—styling trends, materials, performance ideas—all tested on the public in real time. It trained an entire generation of American buyers to expect more than just straight-line speed.

And most importantly, it proved that America could build a sports car—on its own terms.

The C1 isn’t the fastest Corvette. It isn’t the best-handling. It isn’t the most refined.

But it is the most important.

It’s the car that taught Detroit how to dream dangerously. It’s the reason later Corvettes could go toe-to-toe with Ferraris and Porsches without apologizing. It’s the reason the Corvette name still means something seventy years later.

This wasn’t just a car. It was a national experiment in confidence.

The Chevrolet Corvette C1 is flawed, theatrical, occasionally absurd—and utterly essential. It’s the sound of America clearing its throat before learning how to sing properly.

It didn’t arrive perfect. It arrived brave.

And sometimes, that’s far more important.

-