A breathtaking fusion of beauty and brutality, the Ferrari 330 P4 defined an era of racing dominance and design perfection.

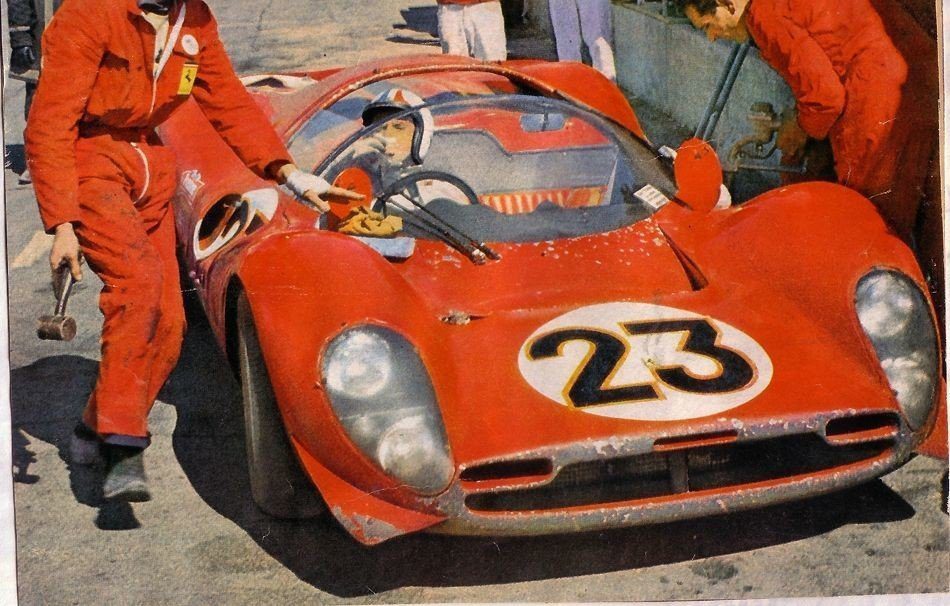

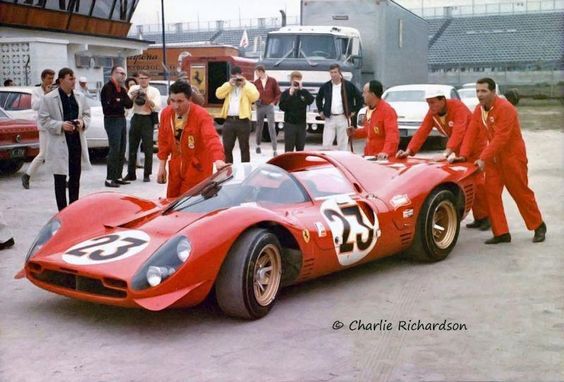

Ferrari 330 P4 at Le Mans in 1967 – a tale of beauty, speed, and crushing disappointment. Picture this: Ferrari shows up to the biggest endurance race on the planet with the P4, a car so stunning it could make a Ford executive cry. And to be honest, they probably did… but not for long.

Because standing in Ferrari’s way was Ford’s GT40 Mk IV – a car designed not out of passion or artistic flair, but out of sheer, unfiltered vengeance. You see, Ford was still steaming from Enzo Ferrari pulling out of their deal to sell Ferrari to them in 1963. Henry Ford II didn’t take that rejection lightly. His response? "Fine, if we can't buy them, we’ll beat them."

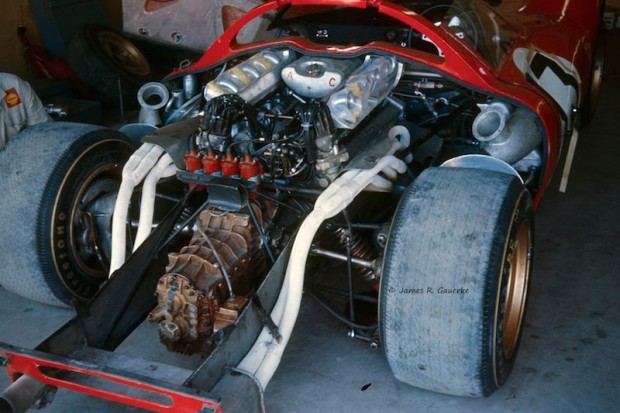

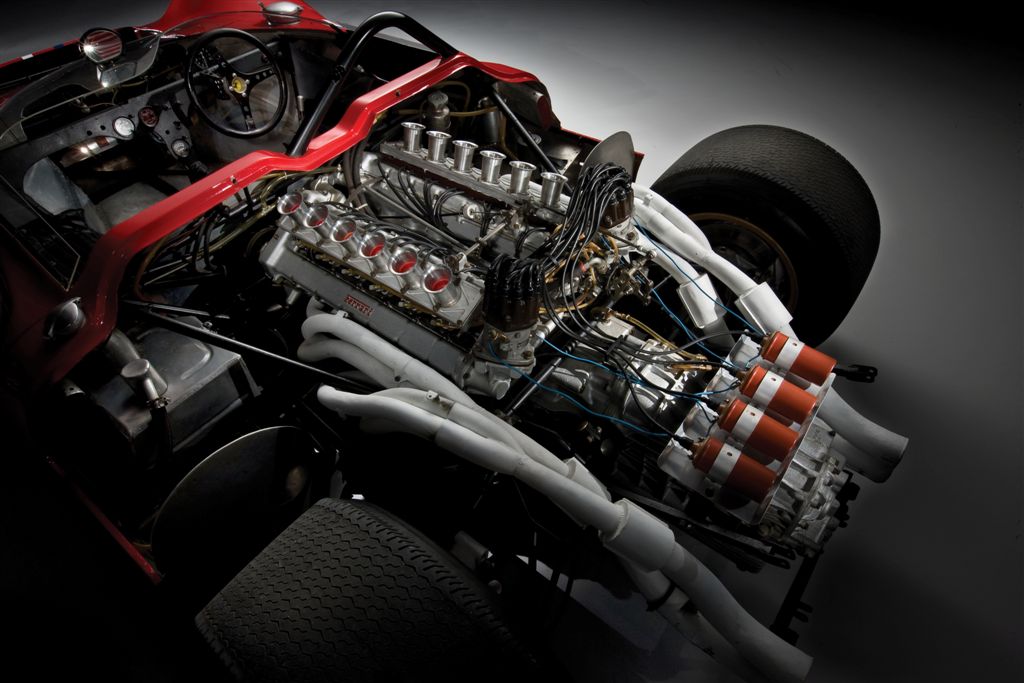

The result? Ford poured enough money into their racing program to probably buy Italy. And by 1967, that cash paid off. The GT40 was faster in a straight line, thanks to a 7.0-liter V8 – essentially a small aircraft engine in a car. While Ferrari’s 4.0-liter V12 sang like Pavarotti, the Ford's V8 roared like a grizzly bear with indigestion.

At Le Mans that year, the Ferrari 330 P4 could dance through corners with grace, but as soon as the track straightened out, the GT40 would blast past like it had been fired out of a cannon. Down the Mulsanne Straight, the GT40 had an advantage that Ferrari just couldn’t match – raw, brutal speed.

Drivers like Chris Amon and Lorenzo Bandini pushed the P4 to its limits, but Ford’s brute-force strategy, combined with Dan Gurney and A.J. Foyt’s flawless drive, secured a 1-2-3-4 finish for Ford. Ferrari? Second place – respectable, but in racing terms, it might as well have been last.

Now, technically, the P4 wasn’t slow. 320 km/h isn’t exactly sluggish, and its lightweight tubular steel chassis wrapped in aluminum panels made it a featherweight compared to the GT40. But lightness only gets you so far when the competition has double your displacement and the aerodynamic profile of a cruise missile.

In the end, the Ferrari 330 P4 was a masterpiece – a car designed by artists and driven by heroes. But against Ford’s nuclear-powered war machine, it just wasn’t enough.

At one point, the 330 P4 actually led the race, proving it wasn’t just a pretty face. But Ford had an ace up their sleeve – or rather, two aces named Dan Gurney and A.J. Foyt. These weren’t just drivers; they were gladiators with grease under their fingernails. Gurney’s tactic? Push the GT40 to its absolute limit – and then some.

The Ferrari fought valiantly. But as the race wore on, it became clear that Ford’s strategy of raw power and relentless speed was paying off. The P4 simply couldn’t match the sheer brutality of the GT40 down the straights. Ferrari’s lightweight, nimble approach was noble – but sometimes, you just need more horsepower.

By the time the checkered flag dropped, Ford had secured a historic 1-2-3-4 finish. Ferrari? Second place – with Bandini and Amon’s P4 trailing behind the leading GT40 by four laps.

But here’s the thing – losing at Le Mans didn’t diminish the Ferrari 330 P4. In fact, it did the opposite. The P4 became a symbol of defiance – proof that even in the face of overwhelming odds and cubic inches, Ferrari could still produce something that stirred the soul.

Today, the Ferrari 330 P4 stands as a reminder that sometimes, the most beautiful cars don’t always win – but they’re the ones we remember.

A tale that plays out like a Shakespearean tragedy, but with more petrol, screaming V12s, and less iambic pentameter. If you’ve seen Ford v Ferrari (or Le Mans ’66 for the purists), you’ll know this isn’t just a race – it’s the race. The one where Ferrari’s pride collided headfirst with American muscle, and the result? Well… let’s just say it was a bad day to be Italian.

By 1967, Ferrari had been the king of endurance racing for years. They’d won Le Mans five times straight earlier in the decade, and Enzo Ferrari wasn’t exactly the sharing type. Enter Henry Ford II – or as I like to call him, "The Man Who Couldn’t Take No for an Answer." After Enzo backed out of Ford’s attempted buyout faster than a Ferrari leaves a starting line, Henry decided to hit Ferrari where it hurt – the racetrack. Because nothing says corporate revenge like spending millions just to humiliate one man.

Now, Ferrari wasn’t about to roll over and let some upstart American car company storm their castle. They responded by crafting the 330 P4 – a car so beautiful that it makes the Mona Lisa look like a rough sketch. Aerodynamic curves? Check. A low-slung body that practically kisses the tarmac? Double check. And under that seductive shell was the heart of a lion – a 4.0-liter V12 producing a modest 450 horsepower. Not bad for the ‘60s.

But here’s the kicker – while Ferrari’s engineers were sculpting art, Ford’s team, led by Carroll Shelby and Ken Miles, were building a hammer. The GT40 Mk IV wasn’t subtle. It was long, low, and packed with a 7.0-liter V8 that generated enough torque to spin the planet in the opposite direction. This wasn’t engineering; this was brute force with wheels.

Fast forward to Le Mans, June 1967. The atmosphere was electric, and Ferrari rolled in with confidence. After all, the P4 had already claimed victories at Daytona and Monza that year, locking out the podium at Daytona in an iconic 1-2-3 finish. But Ford wasn’t about to let that slide.

From the start, the race was an all-out war. Ferrari’s P4, driven by the likes of Lorenzo Bandini, Mike Parkes, and Chris Amon, danced through corners with grace. But as soon as the cars hit the Mulsanne Straight, the GT40s would come thundering past, engines bellowing like distant thunderstorms. It was beauty vs. the beast.

At one point, the 330 P4 actually led the race, proving it wasn’t just a pretty face. But Ford had an ace up their sleeve – or rather, two aces named Dan Gurney and A.J. Foyt. These weren’t just drivers; they were gladiators with grease under their fingernails. Gurney’s tactic? Push the GT40 to its absolute limit – and then some.

The Ferrari fought valiantly. But as the race wore on, it became clear that Ford’s strategy of raw power and relentless speed was paying off. The P4 simply couldn’t match the sheer brutality of the GT40 down the straights. Ferrari’s lightweight, nimble approach was noble – but sometimes, you just need more horsepower.

By the time the checkered flag dropped, Ford had secured a historic 1-2-3-4 finish. Ferrari? Second place – with Bandini and Amon’s P4 trailing behind the leading GT40 by four laps.

But here’s the thing – losing at Le Mans didn’t diminish the Ferrari 330 P4. In fact, it did the opposite. The P4 became a symbol of defiance – proof that even in the face of overwhelming odds and cubic inches, Ferrari could still produce something that stirred the soul.

Today, the Ferrari 330 P4 stands as a reminder that sometimes, the most beautiful cars don’t always win – but they’re the ones we remember.

-