A masterclass in lightweight engineering and driver purity, setting a timeless benchmark that proves true automotive greatness comes from clarity, balance, and restraint.

When people talk about “the greatest road car ever made,” they usually mean “the fastest thing I saw on YouTube yesterday.” That’s understandable. Speed is easy to measure, easy to brag about, and easy to sell. But occasionally, very occasionally, someone builds a car that doesn’t care about the leaderboard, the Nürburgring stopwatch, or how many likes it gets on Instagram. It cares about something far more old-fashioned and far more dangerous: being right.

That is exactly what GMA T.50 is.

This is not a car designed by committee, not a car born from a PowerPoint slide full of market research, and definitely not a car that exists to dominate a spec sheet. It is, quite simply, the final word of a man who has spent his entire life thinking about how cars should be built, and who decided—at the age when most engineers are playing golf—that he would settle the argument once and for all.

To understand the T.50, you have to understand Gordon Murray. And to understand Gordon Murray, you must first accept one uncomfortable truth: most modern cars annoy him.

They’re too heavy.

They’re too complicated.

They’re too tall, too wide, too numb, and too obsessed with numbers that don’t actually improve the joy of driving.

This is the man who designed the Brabham BT46B “fan car,” a Formula One machine so clever it was politely asked to leave the sport after one race. The man behind the McLaren F1, a car that, three decades later, still makes modern hypercars look like bloated tech demos. Murray has never been interested in winning arguments on paper. He wants to win them in reality.

And the T.50 is his closing statement.

The first thing Murray did was ignore almost every trend of the last 20 years.

No hybrid system.

No turbos.

No electric motors filling in torque holes.

No giant touchscreens.

No adaptive suspension modes called “Dragon,” “Track Plus,” or “Unleashed Beast.”

Instead, he asked a very simple question: what happens if you remove everything that doesn’t make driving better?

The result is a car that weighs under 1,000 kg fully fueled. Let that sink in. In a world where family SUVs weigh more than small moons, this thing weighs about the same as a 1990s hot hatch—while producing over 650 horsepower.

That number alone tells you this car exists in a different philosophical universe.

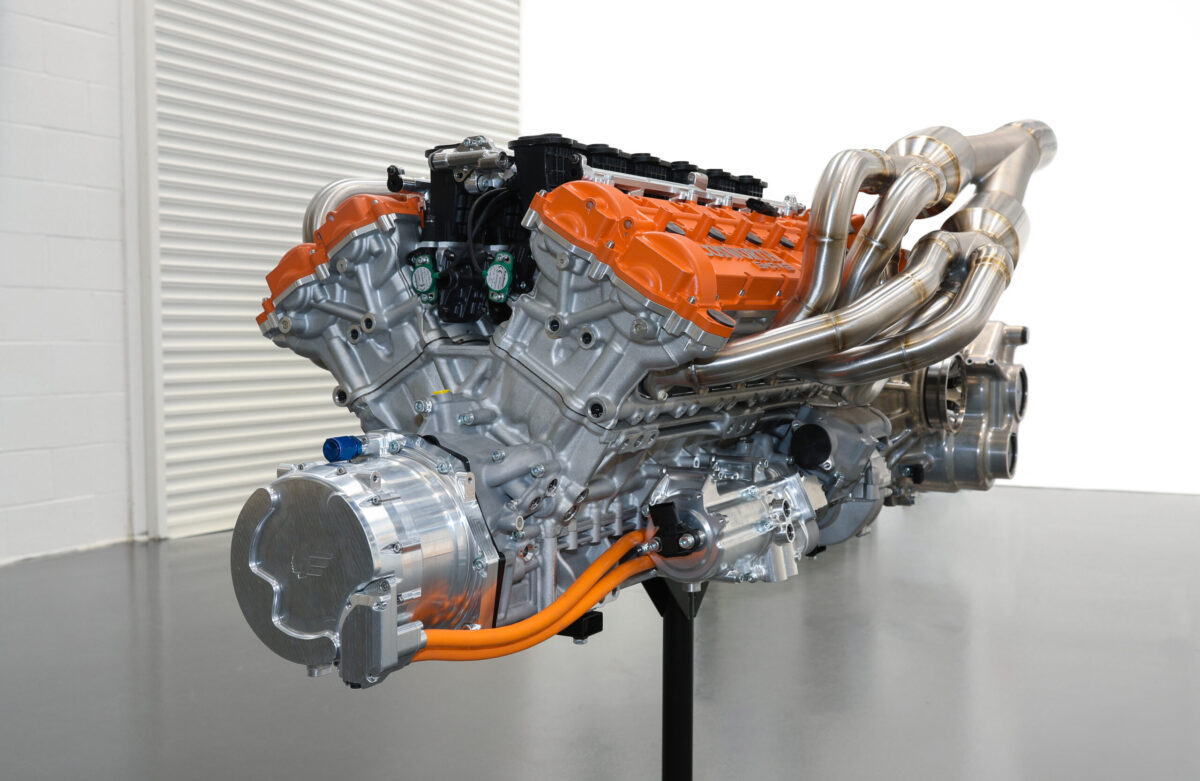

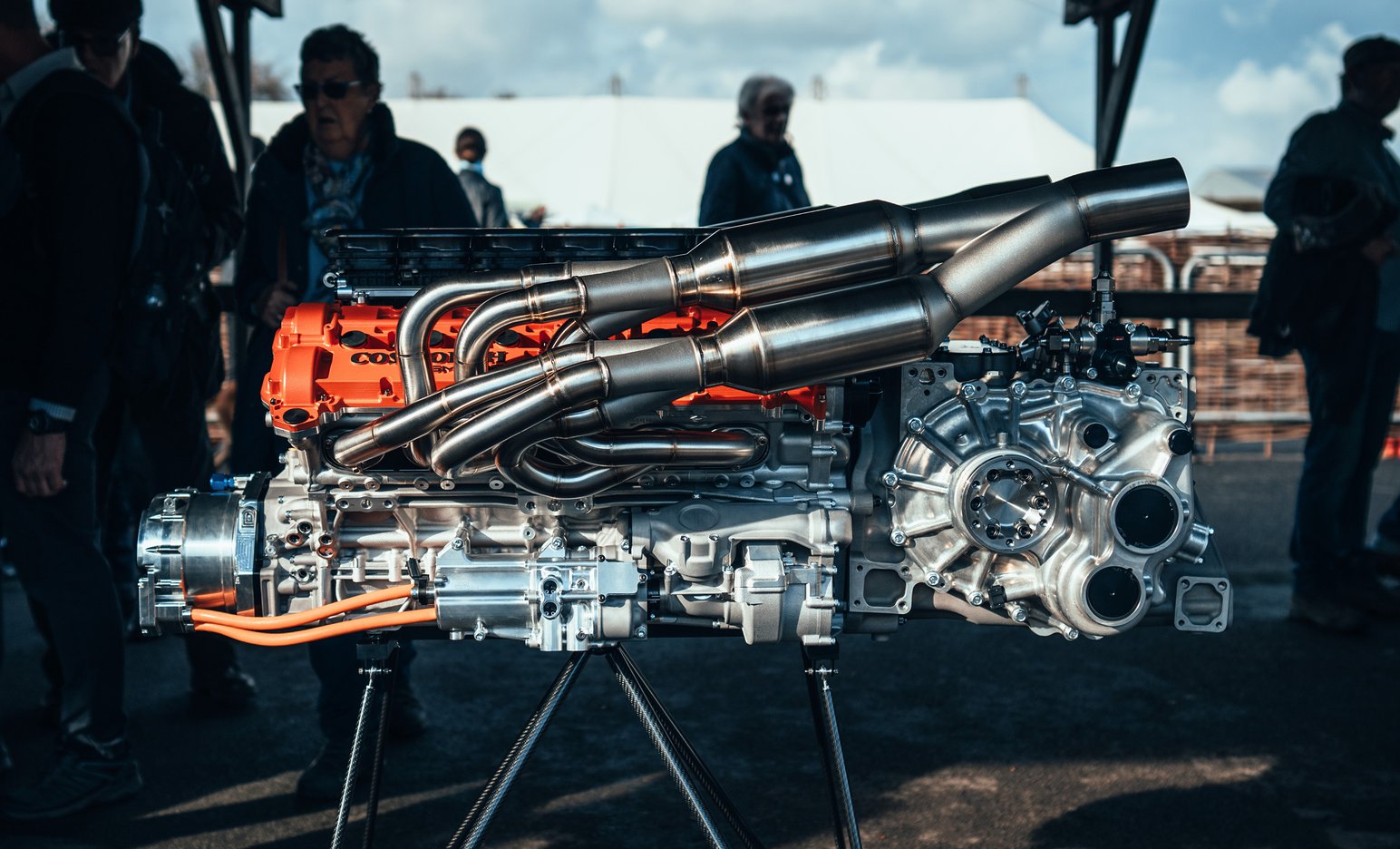

At the heart of the T.50 is a masterpiece: a naturally aspirated V12 developed with Cosworth. It revs to 12,100 rpm. Not “oh wow, that’s impressive” rpm. Motorcycle-embarrassing, spine-tingling, hairs-standing-on-end rpm.

This engine doesn’t shout. It sings. A thin, razor-sharp mechanical scream that builds, and builds, and builds, until your brain starts questioning whether pistons should legally be moving that fast.

There is no turbo lag because there are no turbos. There is no artificial augmentation because there is no need. The throttle response is instantaneous, not because software guessed what you wanted, but because physics agreed with you.

And it’s bolted to a six-speed manual gearbox. Of course it is. Because if you’re going to build the ultimate driver’s car, you don’t remove the driver.

Yes, there’s a fan at the back. And no, it’s not a gimmick.

Murray hates wings. He thinks they’re lazy. Big wings add downforce, yes, but they also add drag, visual clutter, and compromise. The T.50’s solution is beautifully mad: active aerodynamics powered by a 400 mm fan that sucks air from under the car.

This allows the T.50 to generate enormous downforce without massive external aero surfaces. The car can adjust how it behaves depending on what you’re doing: braking, cornering, accelerating. It’s like having a race engineer under the rear deck, constantly tweaking the airflow in real time.

And the best part? You don’t see it working. It just does.

Open the door and everything becomes clear.

You sit in the center.

Not because it’s cool. Not because it’s dramatic. But because it’s correct. Weight distribution, visibility, symmetry—everything improves when the driver is placed exactly where they should be.

Two passenger seats sit slightly behind and to either side, angled inward. You don’t feel like a chauffeur. You feel like a pilot. The view ahead is pure, uninterrupted road. No thick A-pillars. No inflated dashboard pretending to be architecture.

The steering wheel is small, simple, and blessedly free of buttons. The gauges are clear, purposeful, and utterly uninterested in impressing you with animations.

This is a cockpit, not a living room.

On paper, the T.50 is not the fastest hypercar ever built. And Murray couldn’t care less.

What matters is how it feels at 60 km/h. How it communicates grip. How the steering loads up naturally as speed increases. How the brake pedal tells you exactly what the tires are doing.

Modern hypercars often feel like they’re dragging you along for the ride, translating your inputs through layers of software and safety nets. The T.50 does none of that. It trusts you. And because it’s light, everything happens with clarity.

You don’t wrestle it. You dance with it.

This is the difference between performance and connection. One impresses. The other stays with you forever.

This car is not just Gordon Murray’s work. It’s the culmination of decades of collaboration with some of the best minds in motorsport and engineering.

Cosworth’s engineers pushed naturally aspirated technology to a level most people thought was finished. Aerodynamicists revisited ideas from banned Formula One concepts and refined them for the road. Craftsmen obsessed over grams, millimeters, and tactile feel in a way mass-market production simply cannot afford.

Every decision had one test: does this make the car better to drive?

If the answer was no, it was thrown out. No matter how clever it sounded in a meeting.

The T.50 is important not because it’s rare, expensive, or fast—though it is all of those things. It matters because it proves something many people had quietly forgotten:

Progress does not always mean more.

Sometimes it means less weight.

Less interference.

Less noise from everything except the engine.

In an era obsessed with electrification, automation, and removing friction from every experience, the T.50 unapologetically embraces friction—mechanical, emotional, human.

It reminds us that driving can still be an art form.

Every T.50 was sold before most people even saw one in person. That alone tells you everything. This isn’t a speculative asset dressed up as a car. It’s a car serious people wanted to use.

Years from now, when regulations tighten further and internal combustion becomes something you explain to children using museum exhibits, the T.50 will stand as a reference point. Not “the last V12,” but the right way to do it.

It will be spoken of in the same breath as the McLaren F1, not because it chases the same numbers, but because it shares the same soul.

The GMA T.50 is not trying to be the future. It doesn’t need to be. It exists outside trends, outside hype cycles, outside quarterly earnings calls.

It is one man, one philosophy, and one final refusal to accept that driving pleasure must be sacrificed on the altar of convenience.

And that, frankly, makes it one of the most important cars ever built.

-