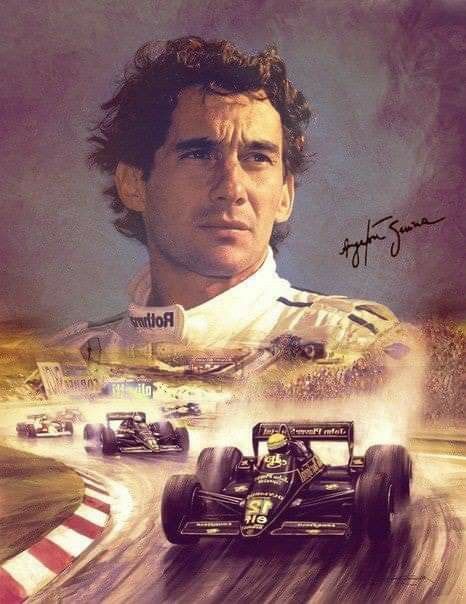

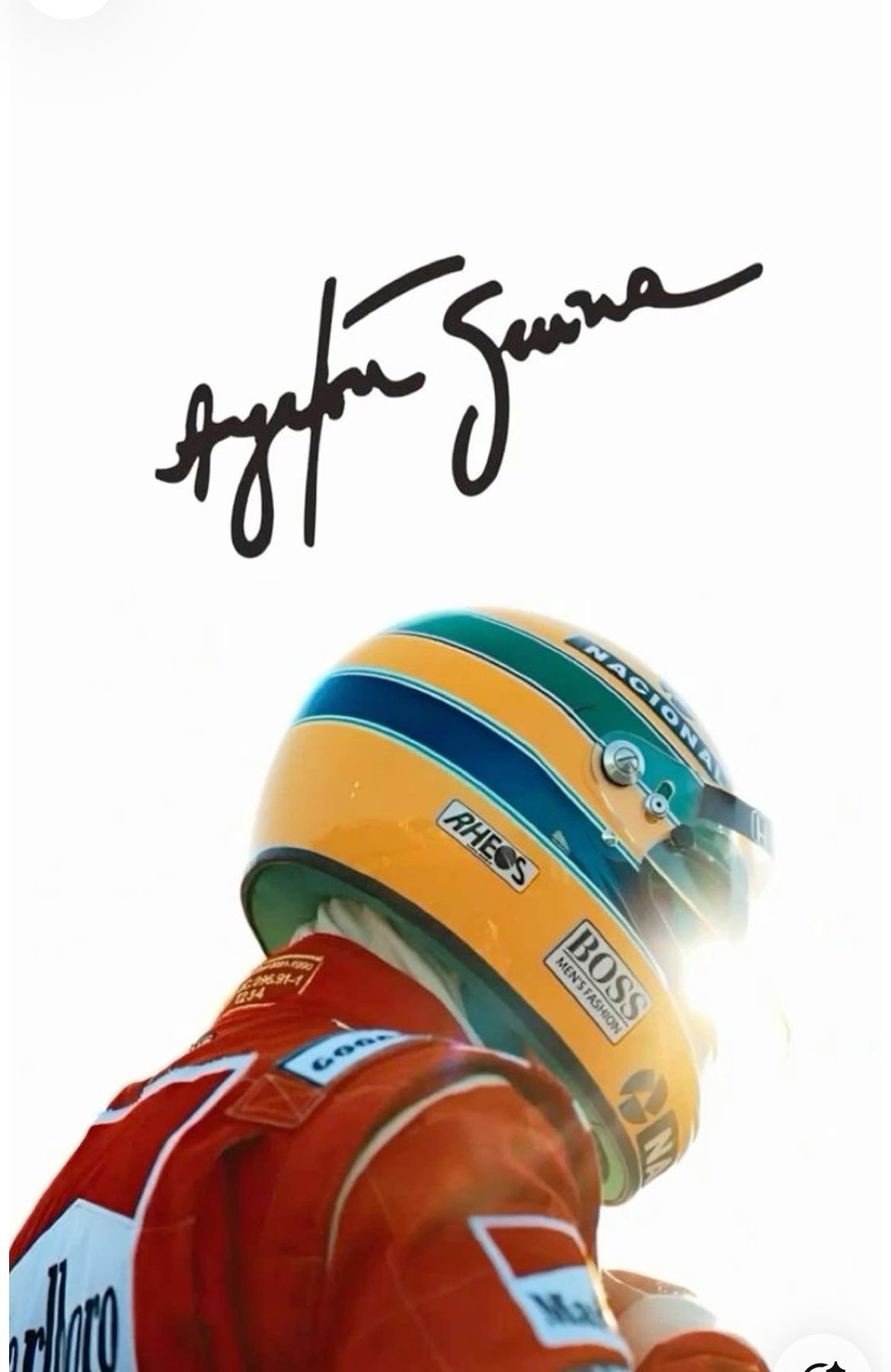

The Alchemist and the Black Thunderbolt: How Senna Turned a Fragile Lotus Into a Formula One Brushstroke of Godlike Brilliance

Imagine the year is 1986: Gérard Ducarouge (Lotus technical director) and Martin Ogilvie (chief designer) — the dynamic Franco-British duo — conjure up the Lotus 98T, a carbon‑fiber and Kevlar monocoque beast with an adjustable chassis so low it’s basically crawling on the track. The shrink‑wrapped chassis sat atop a Renault EF15B 1.5‑liter turbo V6, tuned to spit out around 900 bhp in race trim and an earth‑shattering 1,000–1,200+ hp in qualifying — numbers that would make modern engineers break into cold sweats.

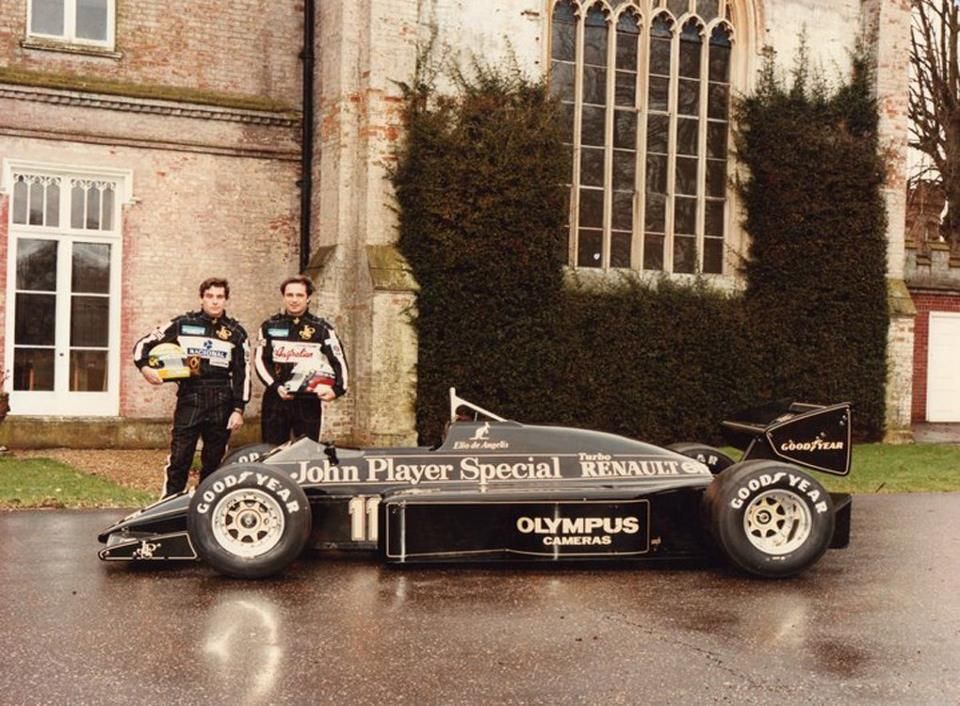

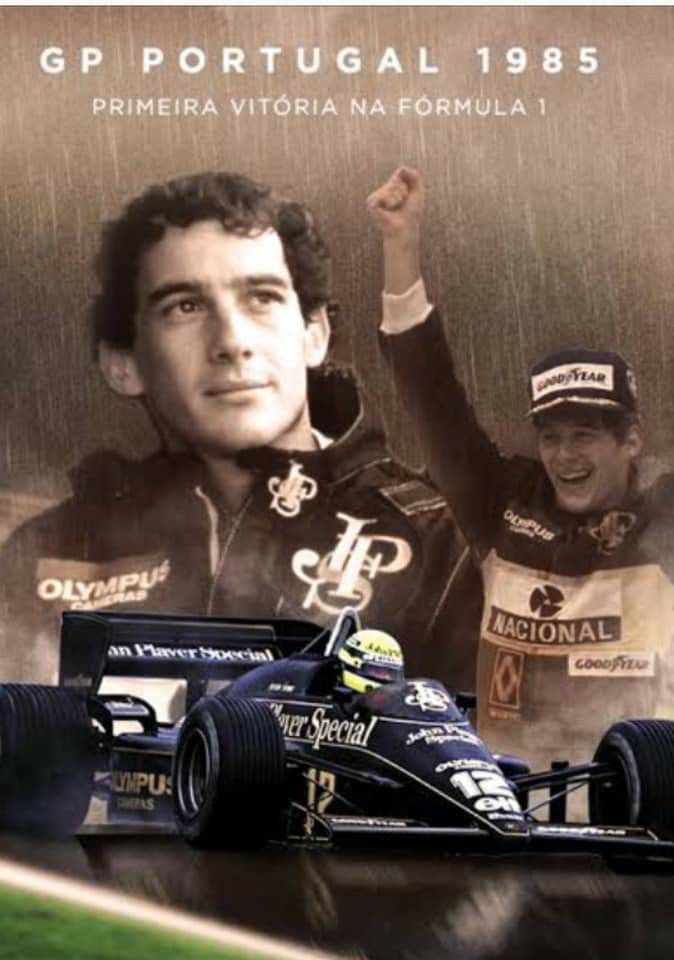

Into this missile climbed Ayrton Senna and brave Scot Johnny Dumfries, but it was Senna who transformed this carbon‑grabber into legend. He grabbed eight pole positions out of 16 races and squeezed two improbable wins in Spain and Detroit—victories of such slender margins that they seemed almost theatrical. Near‑death turbo lag, steering that felt like wrestling a rabid badger, and the sound? Six‑blast turbo howl that sounded like an angry dog gobbling jet fuel.

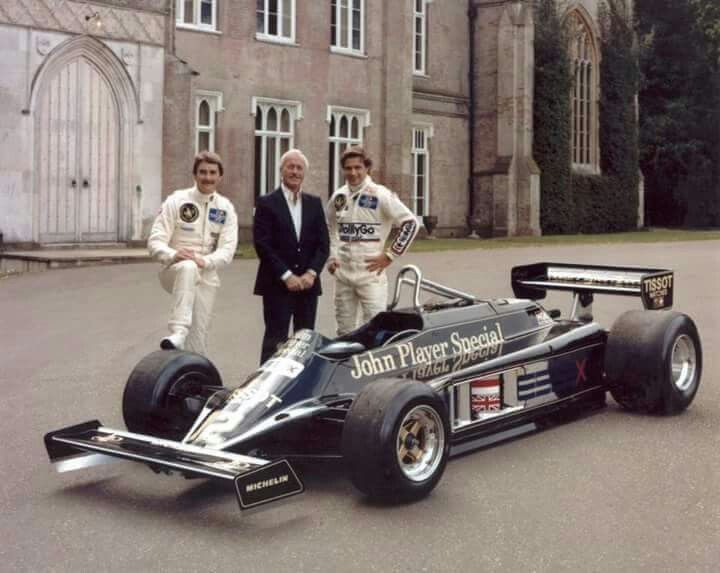

Lotus were no longer the dominant force of yesteryear; Colin Chapman had gone, and Peter Warr held the reins. Ducarouge’s resurrection of truth, though—imposing a lower fuel tank limit (195 litres), reshaped suspension geometry, and pull‑rod double wishbones front and rear—gave the 98T nimbleness few rivals could match.

By the flashy post‑qualifying world of modern F1—traction control, hybrid systems, aero wash—it was a different era entirely. Back then, pre‑emptive throttle modulation was as critical as braking or braking at all. Mansell later quipped you had to stand on the throttle before the apex to allow the turbo time to spool. It was like anticipating lightning—but if you got it wrong… well, your McLaren rival would be dead ahead.

Lotus grabbed third in the Constructors' Championship, beating Ferrari on countback in a season that was as much about grit as horsepower. Senna finished fourth in the driver standings. Renault walked away at year’s end, meaning the 98T became the team’s last Renault‑powered turbo. Next up was Honda and the infamous 99T.

Senna would later refer to his successor as “just a 98T with a Honda engine.” And you can see why—because the 98T wasn’t just a car: it was pure, unfiltered racing electricity. It was dangerous, beautiful, and entirely unforgettable.

Other Story Senna

Let me tell you a story about a man and a machine. Not just any man — Ayrton Senna, the Brazilian sorcerer with eyes like razors and a throttle foot calibrated by the gods. And not just any machine — the Lotus 98T, an unhinged turbocharged dagger on four wheels, dressed in John Player Special black and gold, like a tuxedo for a prizefighter.

In 1986, Senna was just 26, already feared by the paddock and worshipped by the engineers. When he stepped into the 98T, he didn’t just drive it — he possessed it. The car itself was vicious — twitchy, laggy, utterly mental. The turbo delay was so long you could plant a daffodil and watch it bloom before the boost kicked in. But Senna made it dance. He didn’t adapt to the car — he made the car adapt to him.

The 98T's Renault EF15B engine could pump out more than 1,200 horsepower in qualifying trim. Think about that. One thousand. Two hundred. In a car that weighed less than your cousin’s Fiesta. It was fast enough to rip the paint off time itself. The car didn’t have traction control. Didn’t have power steering. Didn’t have mercy. But Senna didn’t need it.

Monaco 1986, qualifying. Senna flung the 98T around the barriers like he was threading a needle during an earthquake. He missed pole by a blink to Alain Prost’s McLaren, but the lap? It was art. Afterwards, engineers gathered around the telemetry like it was scripture. No driver had ever used the throttle like that. Full commitment. Full lunacy. Full Senna.

Detroit, though, was where the legend crystallized. Bumpy, filthy, narrow — it wasn’t a circuit, it was a construction site. Senna drove with such ferocity he lapped half the field. He didn’t win with the Lotus — he dragged it, kicking and screaming, across the finish line like a man carrying an angry lion in a suitcase.

In the pits, Lotus engineers often stood back during debriefs, jaws slightly agape. Ayrton wasn’t giving feedback. He was giving philosophy. He’d describe how the front end “spoke to him” through vibrations, how the throttle needed to “breathe with the car.” Johnny Dumfries, his poor teammate, said trying to match Senna was like “rowing a dinghy behind a battleship.”

And yes, there were politics. Senna refused to share his telemetry with Dumfries. He even vetoed Derek Warwick as a teammate — not out of fear, but because he wanted all the attention on car development. It wasn’t selfishness. It was obsession. The 98T was his canvas, and he wasn’t sharing his brushes.

Lotus themselves were struggling financially, holding on to F1 relevance by their fingernails. But Senna and the 98T bought them another season of glory. Third in the Constructors'. Eight poles. Two wins. Enough to whisper: "Lotus is still alive."

That year also deepened the respect between Senna and engineer Steve Hallam, who later recalled, "With Ayrton, you didn’t just engineer a car. You engineered the feeling of invincibility."

The 98T may not have won a championship. But what it did do was showcase what happens when one of the greatest drivers in human history straps himself into a fire-breathing black missile and decides he wants to bend physics to his will.

-