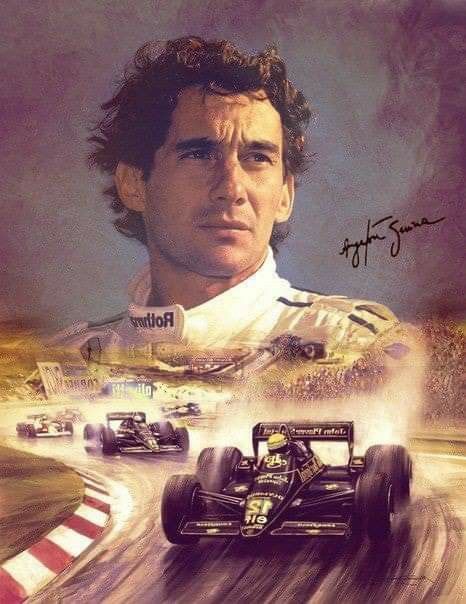

A Brazilian voice in fluent English, carrying Ayrton Senna’s legacy, explains how the MP4/4 became the greatest Formula One car ever.

If you want to understand why the McLaren MP4/4 still makes grown adults go misty-eyed and start talking in hushed tones—like they’ve wandered into a cathedral made of carbon fibre—begin with this: it wasn’t just a racing car. It was a loophole with wheels. A rolling “yes, but what if we…” that turned Formula 1 into a polite annual humiliation for everyone else.

1988 was meant to be the year the turbo monsters were put on a diet. The rule-makers had looked at the previous seasons—cars arriving at corners like guided missiles powered by witchcraft and benzene fumes—and decided enough was enough. Boost was strangled, fuel was slashed, and the turbo era was essentially told, “Right. Finish your drink. Taxi’s here.” Boost capped at 2.5 bar and fuel limited to 150 litres meant everyone would have to think, not just detonate.

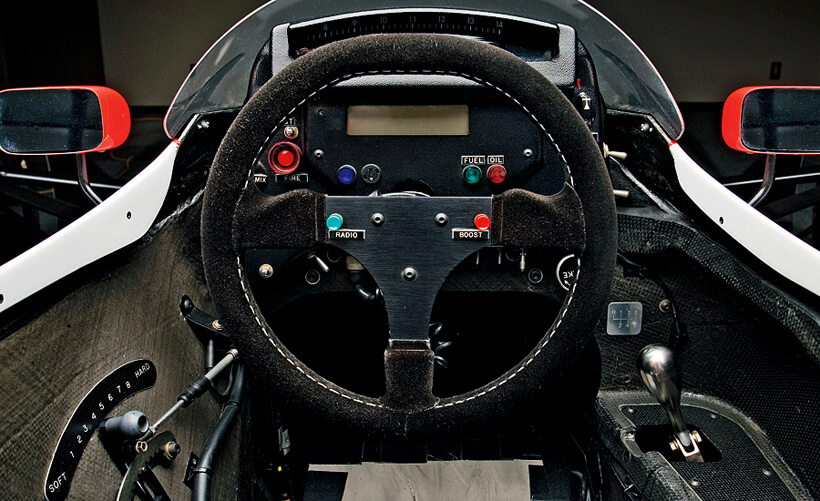

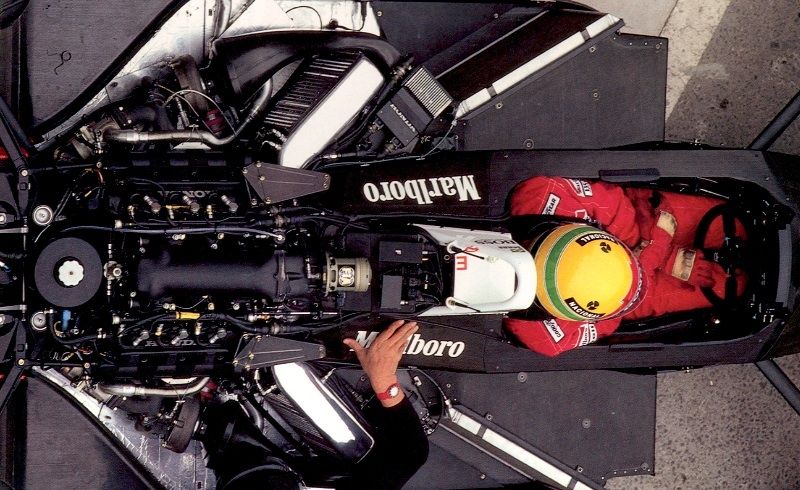

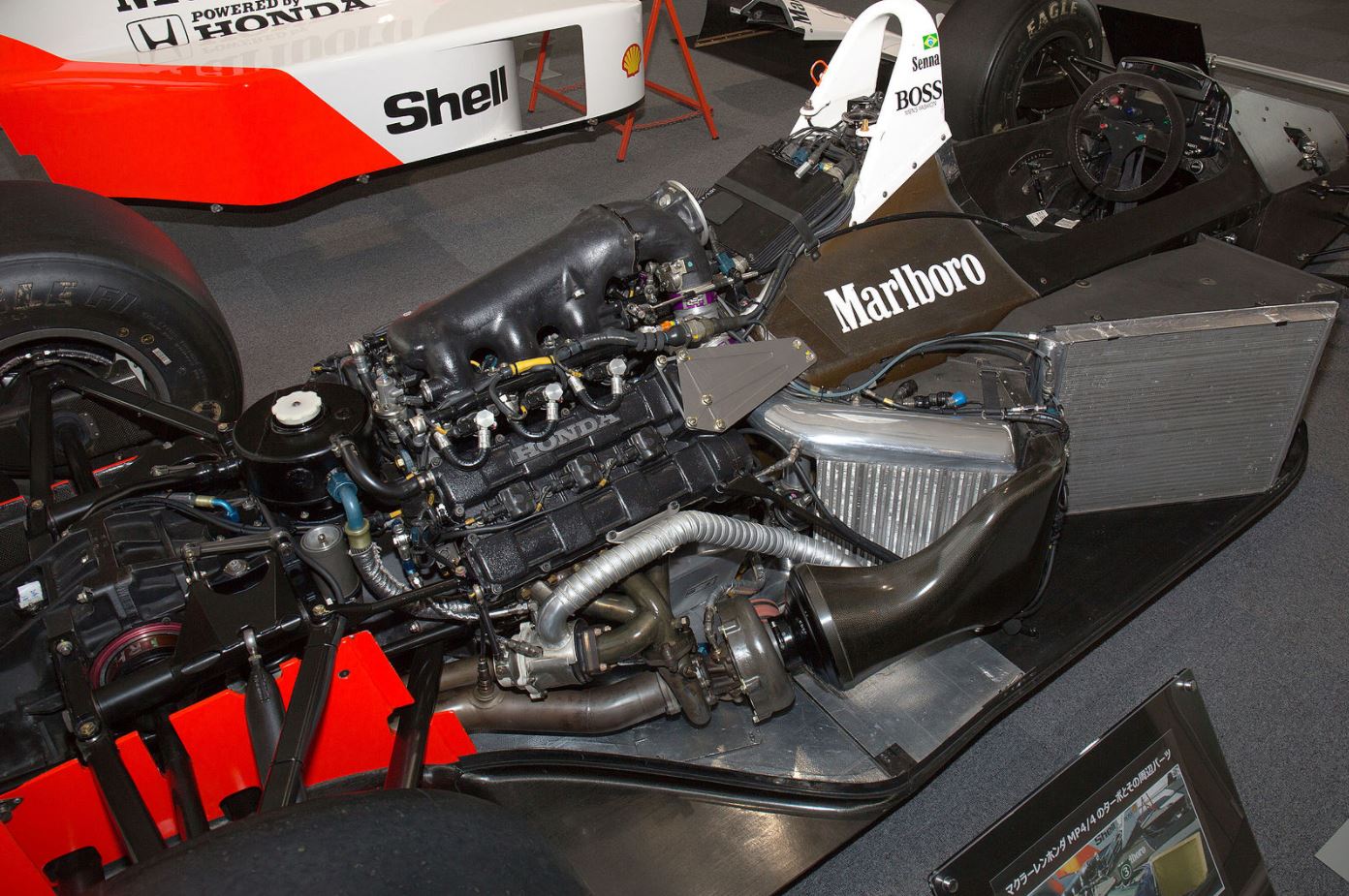

And then McLaren showed up with the MP4/4: so low and so sleek it looked like it had been designed by a man who’d been told air is expensive. The driving position was reclined—properly reclined—so the driver looked less like a gladiator and more like a man trying to watch television while someone shouts lap times at him. That low-line packaging wasn’t just style; it was aerodynamics, centre of gravity, and a very McLaren way of saying, “We’ve read your rules, and we’d like to interpret them creatively.”

Now, whenever a car becomes this dominant, the next argument is always: who actually built the thing? With the MP4/4, this has turned into a sort of engineering custody battle. Steve Nichols is widely credited with leading the design, while Gordon Murray’s influence—particularly the obsession with low profile—gets argued over with the intensity of football fans debating a handball in 1970. Even reputable insiders and historians still spar about how much was Nichols’ clean-sheet brilliance and how much was Murray pushing ideas and processes.

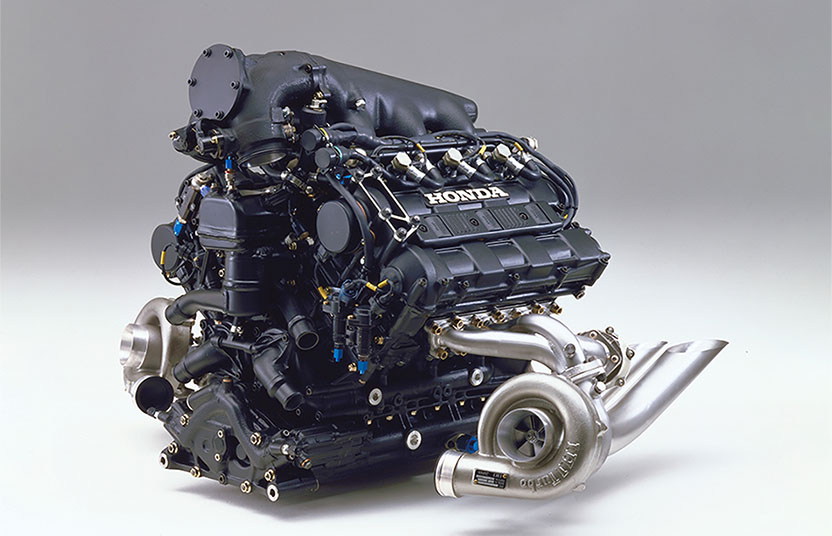

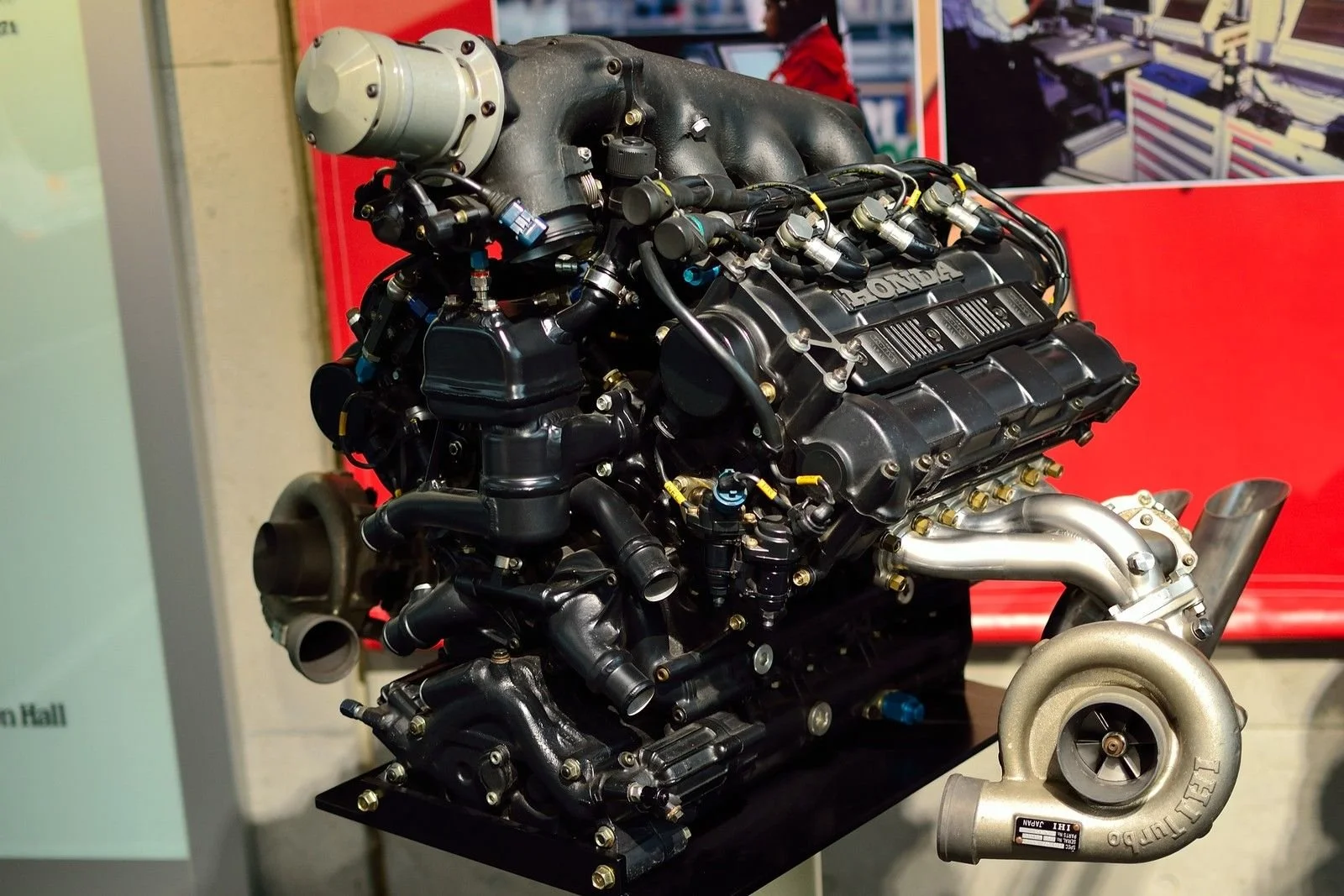

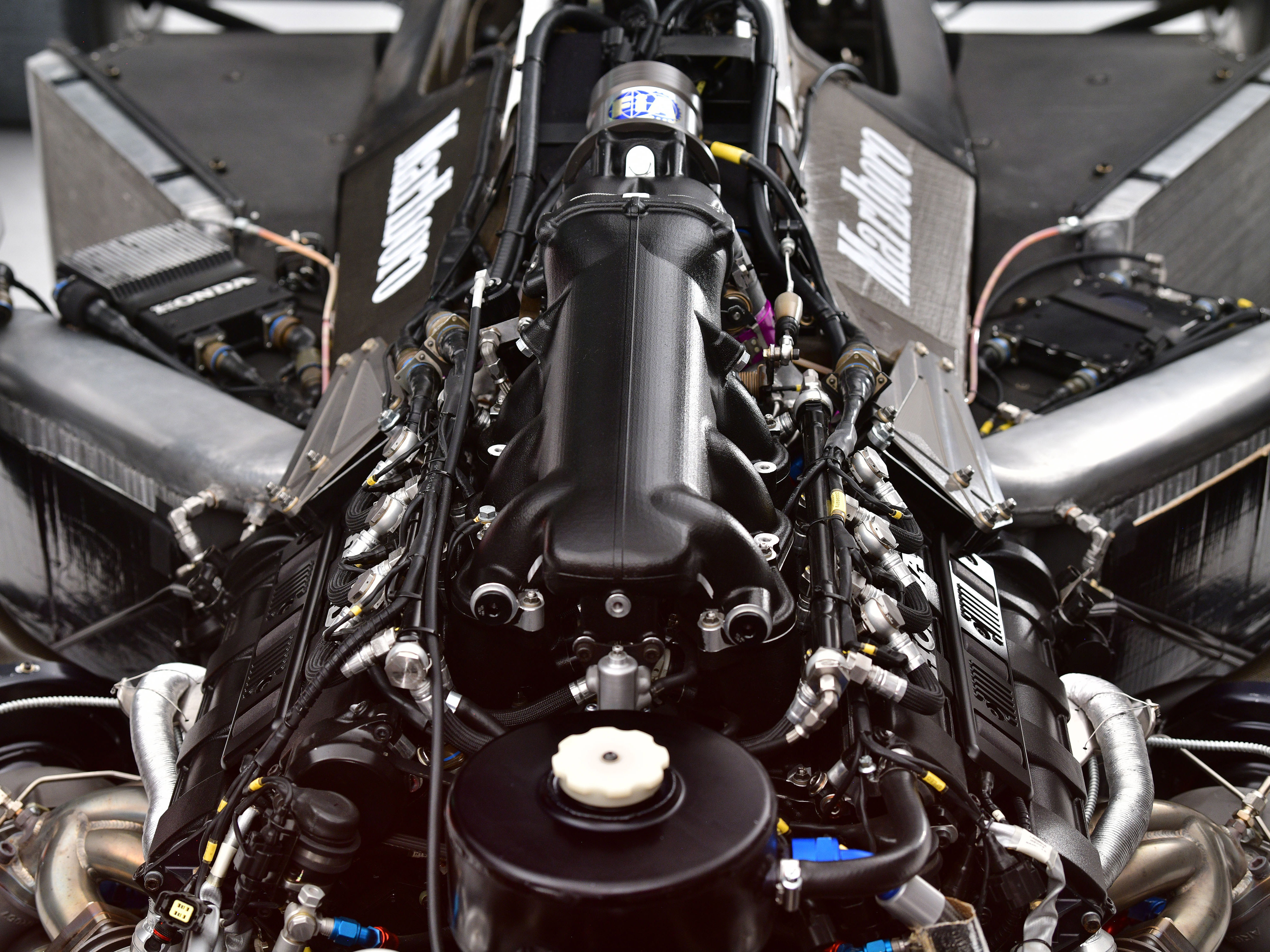

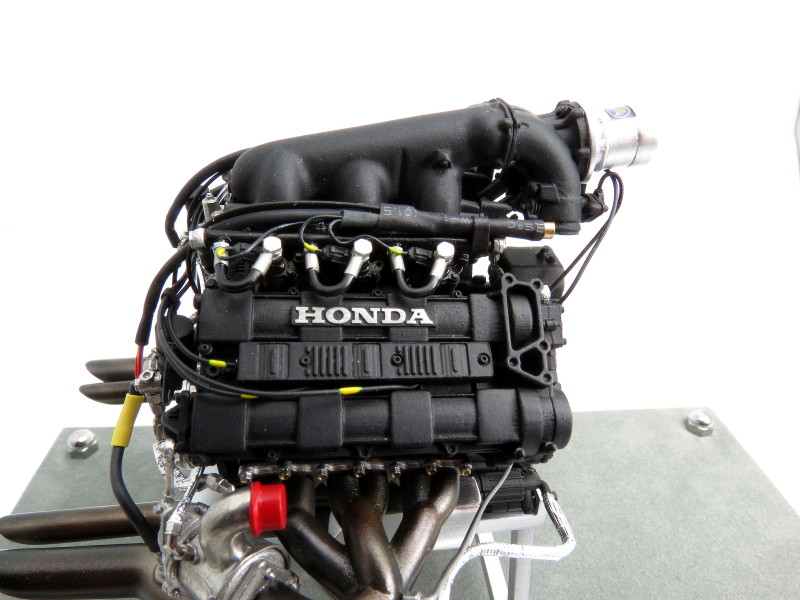

But here’s the more important bit: even the best chassis in the world is just a very fast wheelbarrow unless it’s got an engine that can do the job under the new “please sip your fuel like it’s rare whisky” rules. Honda turned up with the RA168E, a 1.5-litre V6 turbo that wasn’t about headline hysteria anymore—it was about efficiency, drivability, and the kind of relentless engineering stamina you normally associate with Japanese commuter trains. Honda themselves will happily tell you that this engine, in this final throttled turbo year, was a huge part of why the car became a steamroller.

So you have the low-slung McLaren, the clever Honda, and then you add the human element—because of course you do—and what humans. Two of the greatest drivers ever to do it, in the same garage, at the same time, both convinced the other one is an obstacle that has somehow learned French or Portuguese.

Ayrton Senna was the lightning. The impossible reflexes. The man who could find grip on wet paint. Alain Prost was the metronome—clinical, calm, terrifyingly efficient, and quite capable of winning a war using only a clipboard and a raised eyebrow. Put them together in the most devastating car of its era and you don’t get harmony. You get opera. With knives.

McLaren’s management—Ron Dennis, impeccably pressed, relentlessly controlled—tried to run it all like a Swiss watch factory. And in the middle of the emotional blast radius you had people like Jo Ramírez, the team coordinator, whose job description basically became “professional peacemaker between two genius egos travelling at 200 mph.”

Then the season began, and immediately the MP4/4 started behaving like it had read the script. Pole positions, wins, one-twos—week after week the thing simply arrived, bullied everyone, and left. Across the season it won 15 of 16 races, with ten 1–2 finishes, and it took pole at 15 of 16 as well. That isn’t dominance. That’s a polite takeover.

And yes, there was one day it didn’t win. One day the universe briefly remembered it had a sense of drama.

Monza.

Italy, red flags, tifosi, the smell of espresso and impending chaos. Prost retired with an engine failure—rare, but the sort of rare that becomes very common if you’re Ferrari and you can smell destiny. Senna was leading late, cruising toward what would have been a full-season sweep for McLaren, when he came upon Jean-Louis Schlesser, who was lapping in for a one-off Williams appearance. Senna tried to thread the needle, Schlesser didn’t vanish, and the MP4/4 ended in the scenery. Ferrari, with Gerhard Berger, won at Monza—an emotional eruption coming just weeks after Enzo Ferrari’s death. If you wrote it as fiction, people would complain it was a bit much.

But most of the time, the MP4/4 wasn’t losing to drama. It was creating it internally. Because Prost and Senna weren’t simply racing the field; they were racing each other’s reputations. Senna took an extraordinary 13 poles that year—an almost rude display of single-lap brilliance. Prost, meanwhile, kept doing Prost things: finishing first or second with the consistency of a tax bill.

And because Formula 1 loves rules that sound like they were invented during a pub argument, 1988 had the “best 11 results count” system. Which meant you could be astonishingly consistent and still get mathematically mugged by the scoring spreadsheet. Senna’s occasional lower finishes could be dropped; Prost’s relentless second places sometimes couldn’t. It’s the only championship format that can make “being too excellent too often” a disadvantage.

If you want the purest MP4/4 Senna legend, though—if you want the bit that makes people stare into the middle distance—go to Monaco. Senna’s qualifying lap there is still treated like a religious artifact, dissected and replayed as if it contains instructions for levitation. He found time where there wasn’t time. He threaded that red-and-white dart between Armco like he was guided by some private radio channel to God.

And then, in the race, after building a lead that was frankly impolite, he crashed. All on his own. A moment of human fallibility in a season where the car and driver often looked inhuman. That crash—its cause, its psychology, the strange idea that he’d entered some trance and then snapped out of it—has been argued over ever since. Which is fitting, because Senna’s entire appeal was that he made the rational world feel slightly inadequate.

Meanwhile Prost was doing what Prost does: taking the points, taking the wins, and quietly taking notes. The rivalry in 1988 is often remembered as the beginning of the real Senna–Prost war. But in truth it was more like the opening chapter where you can still see both men trying, occasionally, to coexist. Barely. With gritted teeth and immaculate lap times.

And the MP4/4 sat underneath it all like a perfect weapon—so effective it amplified every tiny human difference. When a car is merely good, drivers can blame it. When a car is this good, they can only blame each other. Or themselves. Or, occasionally, the laws of physics for not moving out of the way quickly enough.

The other magic trick of the MP4/4 is that it wasn’t just fast—it was fast under constraints. Those fuel limits and reduced boost were supposed to make turbos awkward, thirsty prima donnas. Yet Honda and McLaren made a machine that could still win while managing consumption like a miser counting pennies. The turbo era was meant to go out with a wheeze. Instead, thanks to this thing, it went out doing a victory lap.

So why does the MP4/4 loom so large today, beyond the statistics? Because it’s one of those rare moments where everything aligns: rules, engineering philosophy, power unit, tyres, drivers, team culture. It’s also a reminder that dominance isn’t always boring—it can be myth-making. You’re not just watching lap times; you’re watching history get written in real time by people who will become legends and, in some cases, haunt the sport forever.

Ron Dennis’ era at McLaren was about precision—about systems, standards, obsessive control. Senna was about faith, instinct, and the conviction that there’s always one more tenth if you’re brave enough to take it. Prost was about intelligence, compromise, and winning the title even if the newspapers don’t clap loudly enough. And wrapped around all of them was a piece of engineering so coherent, so devastatingly “right,” that it made the entire grid look like it had turned up to a gunfight with a baguette.

The MP4/4 didn’t just win races. It set a reference point. Every time a modern team has a monster season, people inevitably say, “Yes, but is it MP4/4 dominant?” That’s when you know you’ve become more than a car. You’ve become a measuring stick. A legend.

And if you listen closely, even now, you can almost hear it: that tight, urgent turbo V6 note; the wastegate chatter; the faint sound of two geniuses arguing in different languages about who deserves the front wing spec.

Because that’s the final truth of the MP4/4. It wasn’t built to be loved. It was built to win. The fact that it became adored—revered, even—was simply collateral damage.

-