A boxy Japanese sedan that quietly humbled Europe, birthed the GT-R legend, and taught the world that precision, racing pedigree, and stubborn engineers can change automotive history forever.

The funny thing about the 1968–1972 Nissan Skyline is that, on paper, it looks about as exciting as a filing cabinet with hubcaps. Boxy, upright, sensible… the sort of thing a mid-level accountant in Yokohama might drive to the office before going home to iron his socks. And yet this same shape, this little corrugated shoebox, quietly rewired Japan’s idea of what a car could be – and scared the life out of European brands that thought they had “driving passion” trademarked.

To understand this Skyline, you have to rewind a few years, back to when it wasn’t even a Nissan. It was a Prince – built by Prince Motor Company, whose engineers were far madder than the name suggests. In 1964 they turned up at the Japanese Grand Prix at Suzuka with a sedan, the Skyline GT, that had been stretched at the nose just to ram in a straight-six. Against it: a mid-engined Porsche 904 Carrera GTS, a proper racing knife. And yet, for one glorious lap, Tetsu Ikuzawa in his Skyline actually passed the Porsche, while teammate Yoshikazu Sunako chased it home to second place and the other Skylines filled the top six. Japan lost the race, but gained a legend – and the Skyline discovered it rather liked humiliating Europeans.

Prince then did what any sane, totally not-obsessed company would do: they built a full prototype racer, the R380, to go back and beat the Germans properly. Designed under Shinichiro Sakurai, the car used a two-litre GR-8 straight-six and, in 1966, finally thrashed Porsche at Fuji. Then Prince was swallowed by Nissan – but Sakurai and his racing lunatics went with it, bringing the R380 project and its engine with them. That racing motor would evolve into the S20, the heart of the Skyline GT-R. So yes, the “family sedan” you’re looking at is powered, genetically speaking, by a purpose-built prototype that once went to war with Porsche.

In 1968 the third-generation C10 Skyline appeared, now officially a Nissan. No more Prince badges, but the DNA was still there. The basic cars used modest four-cylinder engines, came as sedans, wagons and eventually a hardtop coupé, with MacPherson struts up front and semi-trailing arms at the back – very modern stuff for a Japanese saloon of the era. It was supposed to sit above the Bluebird as the “sportier” sedan in a respectable, grown-up way. Then someone in the motorsport department clearly said, “What if we stopped pretending to be respectable?”

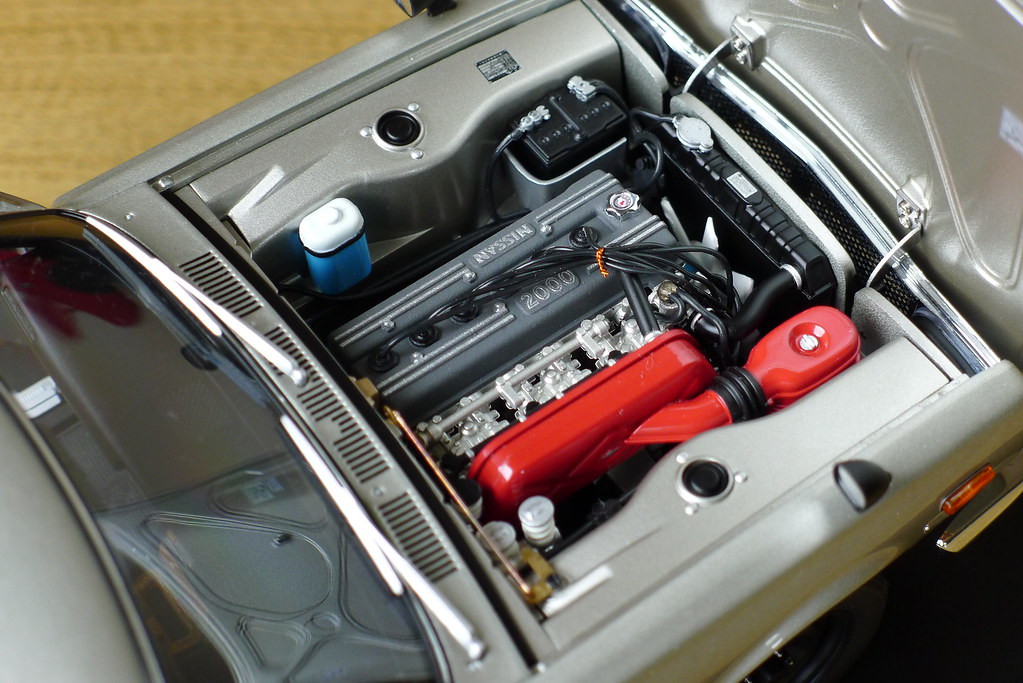

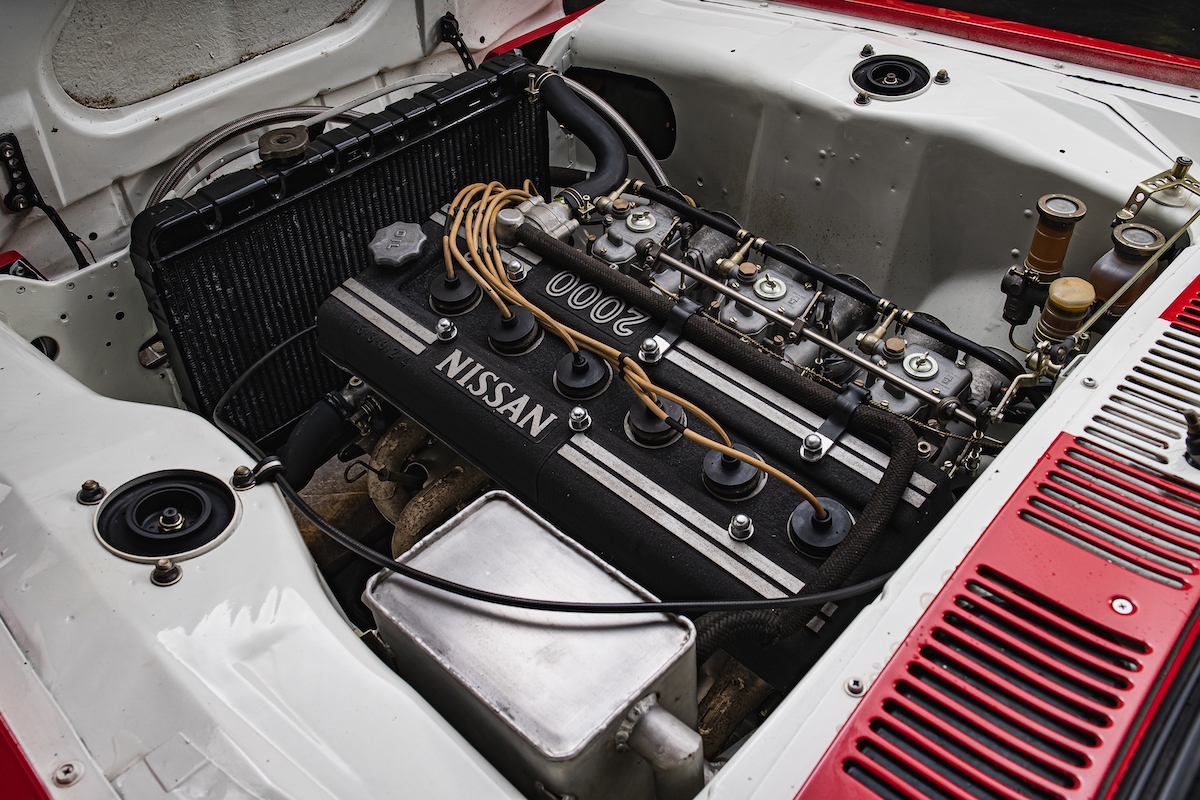

The answer arrived in 1969: the Skyline 2000GT-R, chassis code PGC10. Under the bonnet was the now-road-legal S20 – a 2.0-litre, twin-cam, 24-valve straight-six with triple side-draft carbs, derived from the R380’s racing GR-8. It revved to 7,000 rpm, made about 160 hp and around 180 Nm, and sounded like an Italian opera singer gargling cutlery. Power went to the rear through a five-speed manual and a limited-slip diff. The suspension was stiffened, the ride height dropped, and unnecessary fluff was binned to save weight. This was a homologation special wearing a business suit.

Then, because apparently the sedan humiliating everything on track wasn’t enough, Nissan released the KPGC10 two-door hardtop. Shorter wheelbase by 70 mm, around 20 kg lighter, even more focused. Same S20 shrieking away up front, same rear-drive layout, but the stance and proportions finally matched the intent. From some angles it looked like a tiny, squared-off muscle car someone had washed too hot and shrunk in the tumble dryer – perfectly.

On track, the 1969–72 GT-Rs didn’t just win; they erased the opposition. The sedan version racked up 33 victories in less than two years; add in the coupé and you land on that famous tally of roughly 50 wins by 1972, including a run where it won 49 of its first 50 races. Drivers like Motoharu “Gan-san” Kurosawa turned the Hakosuka into a guided missile, scoring multiple wins himself and doing it with such metronomic precision that Sakurai reportedly described him as “an instrument” rather than merely a driver. This was the era when Skylines battled everything from Mazda rotaries to Toyota 1600GTs and even the odd Porsche – and mostly walked away smirking.

The nickname, of course, was Hakosuka – “hako” for box, “suka” from Skyline. It’s affectionate and slightly mocking, like calling Mike Tyson “Cuddles.” Underneath that square-cut body, the recipe was pure enthusiast catnip: front-engine, rear-drive, independent rear suspension, disc brakes up front, a snick-snick five-speed and just enough tyre to make you work for every lap. Inside, it was sparse: no luxury, just thin door cards, simple gauges and a three-spoke wheel. The sort of car that doesn’t pamper you; it dares you.

Meanwhile, the ordinary C10 Skylines – the 1500s, 1800s, 2000GTs and GT-Xs – quietly did the school run, carried briefcases and shopping, and rusted away in the salt, never knowing they shared bones with a touring-car monster. They were the respectable cousins at a family reunion, carefully ignoring the tattooed relative in race boots who arrives late smelling of race fuel and victory.

Then racing politics and the oil crisis came along, and in 1972–73 the party ended. Nissan pulled back from racing, emissions rules tightened, and the GT-R badge went back into its cave for 16 years. By then Sakurai had handed the Skyline project on to his protégé Naganori Ito, who would later resurrect the GT-R as the R32 and unleash “Godzilla” on the world. But all of that only happened because this humble C10 proved that a Japanese sedan could go door-to-door with European exotica and win.

Fast-forward to today and the Hakosuka’s gone from workhorse to worship object. Only around 1,945 GT-Rs were built, sedan and coupé combined, and survivors are now deep into six-figure territory at auction. Collectors in Japan, the US and Europe bid each other into financial ruin over the clean ones. Some are restored by obsessive specialists and even Nissan’s own restoration teams; others live pampered lives in climate-controlled garages, coming out only for concours events and track days where younger GT-Rs pay their respects.

Pop culture eventually caught up. Paul Walker put a silver Hakosuka on the big screen in Fast Five, quietly telling a whole generation of kids that the grandfather of the R34 existed – and was unbelievably cool. Jay Leno, a man who owns more cars than some small countries, went on television and was visibly surprised by how savage a four-door GT-R felt when you actually rang it out. When a car can impress both Hollywood and a man whose daily driver collection includes steam cars, you know you’re dealing with something special.

So what is the 1968–72 Skyline, really? It’s the moment Japan stopped asking for permission. A boxy sedan, engineered by a stubborn ex-Prince team led by Sakurai, sharpened on the circuits by men like Sunako, Ikuzawa and Kurosawa, and powered by an engine that started life trying to beat Porsche. It looks modest, almost shy, but underneath it’s all revs, grip and murderous intent.

Everyone bangs on about the R32, the Nürburgring times, the PlayStation generation. But without this quietly furious shoebox proving that a Japanese family car could dominate touring-car racing, there would be no Godzilla, no cult, no posters, no internet arguments about boost pressure. The Hakosuka is the patient zero of an obsession that still hasn’t cooled down.

It’s not just a classic. It’s the calm, square-shouldered samurai who taught the rest of the Skyline clan how to draw a sword.

-

Motoharu Kurosawa

Japanese racing driver and touring-car legend