A machine born in an age that believed dignity mattered, comfort was a virtue, and progress did not require shouting.

A long, affectionate study of the Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud II, told with dry British humour and mechanical reverence.

There are cars that want to be admired for their speed. Others demand praise for their cleverness. And then there are a very small number that simply expect obedience. The Silver Cloud II belongs firmly in the last category. You do not “drive” one so much as you agree to escort it through the world while it quietly judges you.

At first glance, it looks like the sort of thing that should be parked outside a country house whose owner owns several tweed jackets and at least one disgraced ancestor. Long, upright, gleaming with the confidence of a nation that still believed tea could solve most international problems, the Silver Cloud II doesn’t shout. It clears its throat. And the world listens.

To understand this car, you have to understand the mindset of the late 1950s. Britain was rebuilding, the Empire was quietly slipping out the back door, and Rolls-Royce, in its serene denial of all this, decided that the correct response was to build the most civilised motor car possible.

Not the fastest. Not the most advanced. The most correct.

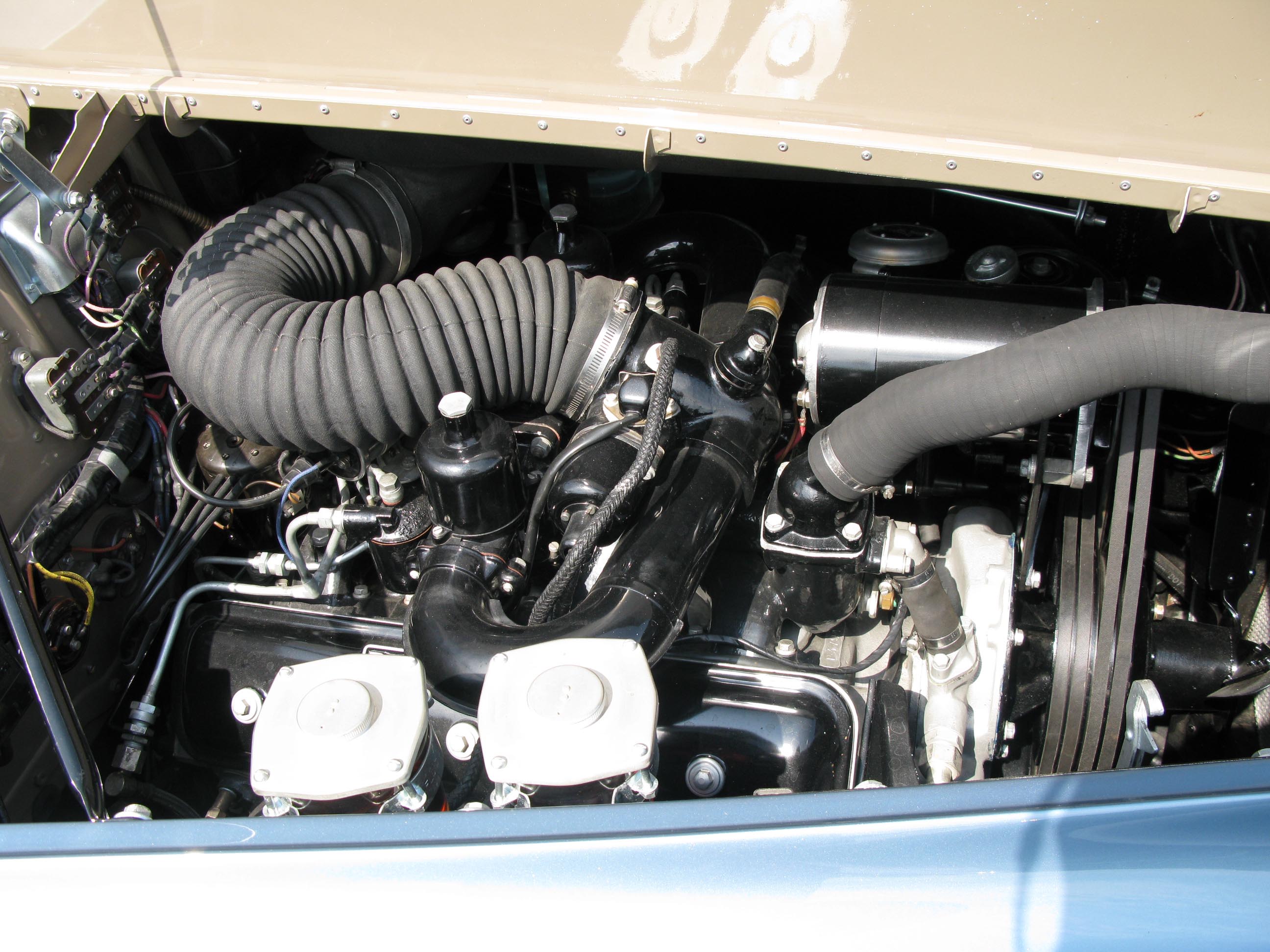

The Silver Cloud II arrived in 1959, replacing the original Cloud with what engineers might describe as “a very discreet earthquake” under the bonnet. Out went the old straight-six. In came a 6.2-litre V8, sourced from across the Atlantic but re-educated in Crewe like a wayward public-school boy.

It was an engine that did not rev. It did not snarl. It did not announce itself. It simply existed, producing torque in the same way gravity produces downwards.

Let’s talk about that V8, because it is the heart of the Cloud II’s quiet genius. Officially, Rolls-Royce refused to publish power figures. When asked, they famously replied that the output was “adequate.”

This was not arrogance. This was philosophy.

The engine was tuned not for drama, but for smoothness so complete that passengers would struggle to tell whether the car was accelerating or whether the Earth itself was rotating more quickly beneath them. Throttle inputs feel more like polite suggestions. You ask. The car considers. Then it complies, calmly, without fuss, and usually without any perceptible change in engine note.

At motorway speeds—if such a thing can be said without offending the car—it feels utterly unstrained. Not quick, but inevitable. Like time passing.

Power is delivered through a four-speed automatic gearbox that behaves less like a machine and more like a well-trained butler. You never feel a gear change. You merely notice that you are now travelling at a different pace than before.

This is not a car that rewards aggression. Stamp on the throttle and it will still accelerate, but with the faint air of disappointment one might reserve for a guest who has asked for ketchup with roast beef.

Steering is light, deliberately so. Feedback is minimal. Not because the engineers couldn’t provide it—but because they didn’t see why you’d want to feel the road. Roads, after all, are a nuisance between destinations.

Much is said about the Silver Cloud’s ride, and rightly so. It does not so much absorb bumps as negotiate treaties with them. Imperfections in the road surface are acknowledged, considered, and then politely ignored.

This is not the floaty, vague softness of something poorly damped. It is controlled, dignified, and deeply reassuring. The car never feels nervous. It never fidgets. It simply proceeds, untroubled, like a bishop late for lunch.

.jpeg)

Corners are taken with composure rather than enthusiasm. Body roll exists, but it’s slow and predictable, as if the car is leaning into a thoughtful remark rather than attacking a bend.

Inside, the Silver Cloud II is less “car interior” and more “Edwardian drawing room that has learned to move.”

The seats are broad, welcoming, and upholstered in leather that seems to have been fed a steady diet of respect. The wood veneer—real wood, polished to within an inch of its life—feels less like decoration and more like tradition made tangible.

Controls are sparse and deliberate. No flashing lights. No gimmicks. Everything is where it should be, because someone spent months deciding where that was.

And silence. Oh, the silence.

At idle, you genuinely have to look at the instruments to confirm the engine is running. At speed, wind noise is hushed, road noise subdued, mechanical intrusion almost nonexistent. Conversations occur in normal tones. Arguments are discouraged by the surroundings.

Driving a Silver Cloud II does something curious to your personality. You slow down—not just physically, but mentally. You stop rushing. You start allowing gaps. You wave people through junctions.

Partly because the car encourages patience. And partly because you realise that arriving thirty seconds earlier achieves nothing if you do so without grace.

Other drivers notice you. Not in the way they notice a supercar, but with a kind of respectful curiosity. Some smile. Some stare. A few older gentlemen nod, as if you have upheld a standard.

You are not anonymous in this car. You are representing something—even if you’re not entirely sure what.

The exterior design is conservative in the way a Savile Row suit is conservative. It does not chase trends. It assumes trends will come and go while it remains.

The tall grille, crowned by the Spirit of Ecstasy, is not there to look aggressive. It is there to look correct. The long bonnet suggests calm confidence. The roofline is upright enough to preserve dignity even when removing a hat.

Nothing is excessive. Nothing is theatrical. And that is precisely why it works.

This is a car that looks expensive not because it is flashy, but because it clearly did not care whether you noticed.

The Silver Cloud II became a favourite of industrialists, statesmen, and entertainers who had already passed the point of needing validation. It was not a car for aspiring tycoons. It was a car for those who had arrived and were now slightly tired.

It appeared outside embassies, hotels, and private residences with gravel driveways. It was often chauffeur-driven, but crucially, it didn’t need to be. Owners could drive themselves without feeling underdressed or overexposed.

It projected authority without menace. Wealth without vulgarity. Power without urgency.

Let’s be clear. This is not a car for the faint-hearted or the casually curious. Maintenance is not cheap. Parts are not plentiful. Expertise matters.

But those who own one rarely complain. Because ownership is not transactional. It is custodial.

You don’t feel like you own a Silver Cloud II. You feel like you are looking after it for the next person. Possibly someone not yet born. That sense of stewardship is part of the appeal.

When properly maintained, the car is remarkably robust. It was built at a time when failure was considered impolite.

Today, the Silver Cloud II occupies a fascinating place in the collector world. It is not the rarest Rolls-Royce. Nor the most valuable. But it is one of the most complete.

It represents the last moment before modern regulations, changing tastes, and corporate evolution softened the edges of old-world luxury. It is the end of an era where refinement was defined not by technology, but by restraint.

Values have risen steadily, but ownership is still more about appreciation than speculation. People buy these cars because they love what they represent—not because they expect a return.

In a world obsessed with speed, data, and constant improvement, the Silver Cloud II feels almost rebellious. It suggests that perfection is not about adding more—but about knowing when to stop.

.jpg)

It does not try to impress you. It assumes you already understand.

And perhaps that is its greatest achievement. The Silver Cloud II does not demand admiration. It simply deserves it.

-

Isambard Kingdom Brunel

British engineer and industrial designer