The Suzuki Escudo Hillclimb is a wild, physics-defying monster built by fearless engineers and driven by Monster Tajima to conquer Pikes Peak with absurd power, unhinged aero, and legendary determination.

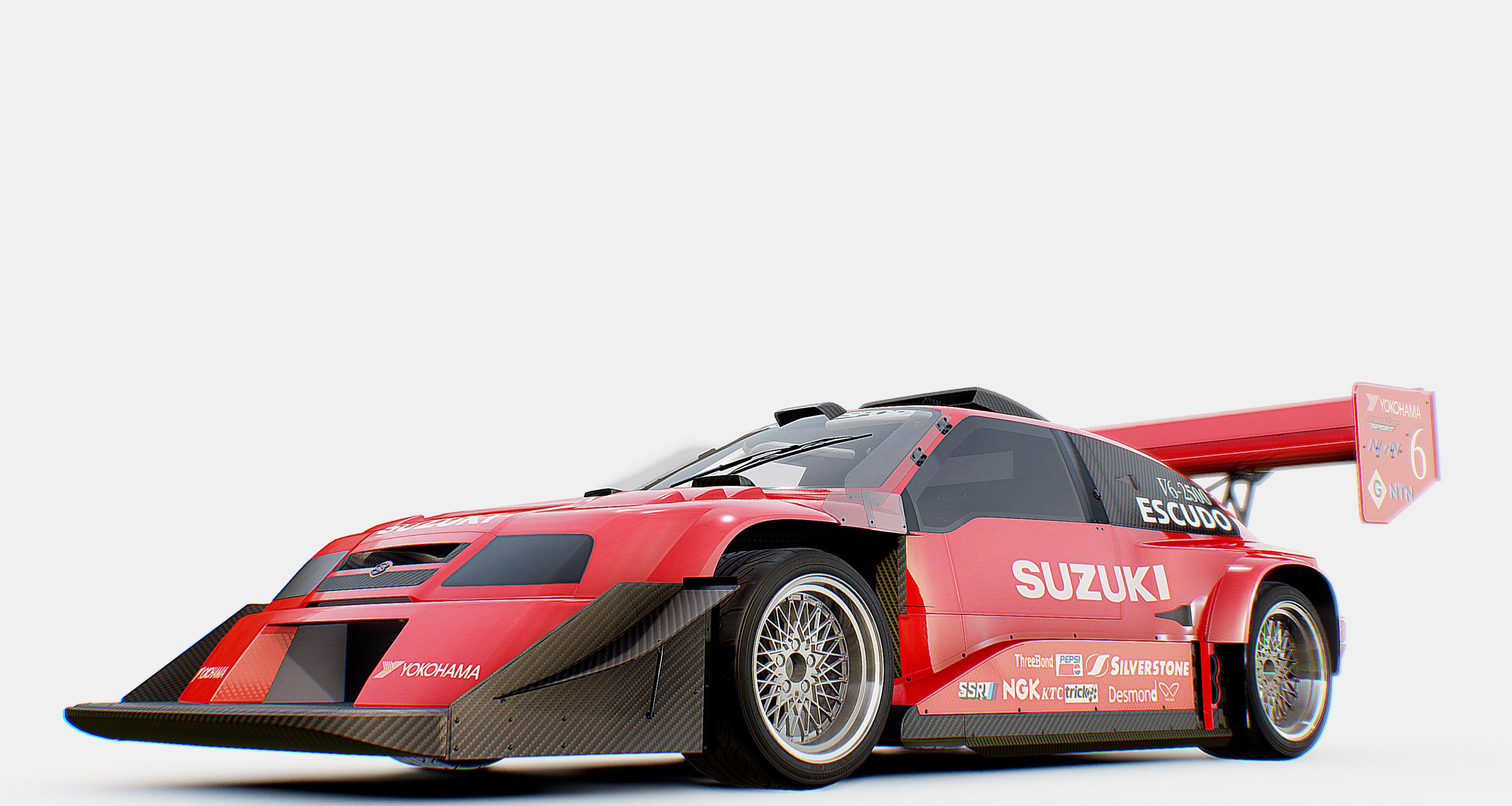

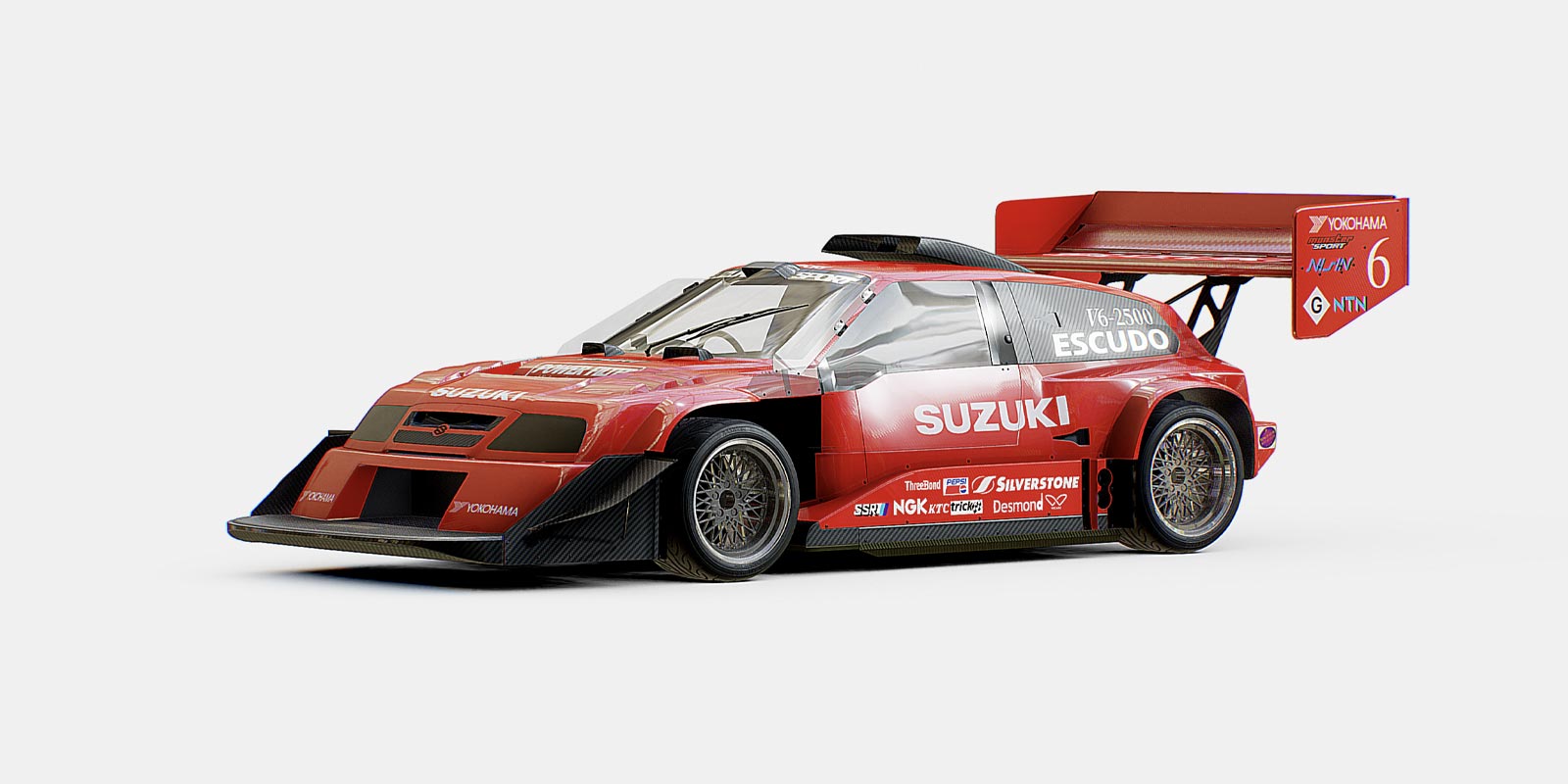

If there is a machine that perfectly illustrates the moment a group of engineers collectively snapped, it is the 1998 Suzuki V6 Escudo Pikes Peak Special. This is not a car. This is a weaponized misunderstanding of physics. The ordinary Suzuki Escudo is a cheerful, dependable SUV — the kind of vehicle used for school runs, fishing trips, and people who believe “sport mode” is something their shoes have. The ’98 Pikes Peak Special, however, looks like someone fed the normal Escudo a bathtub of steroids and emotionally neglected it until it rebelled.

Everything about this machine screams: “I refuse to behave.”

Let’s start at the beginning.

Suzuki’s involvement in hillclimbing had always been the story of a modest automaker punching well above its weight. But the moment the Unlimited Class at Pikes Peak became a corporate playground for lunatics with budgets and torque, the brand decided subtlety was a waste of oxygen.

Enter Nobuhiro “Monster” Tajima, a man whose personal definition of “safety” is best described as “optional.” Tajima wanted a machine that would not simply climb the mountain — he wanted one that would psychologically break it.

So Suzuki’s engineers rolled up their sleeves and built something completely out of proportion.

The 1998 V6 Escudo Pikes Peak Special doesn’t share a single philosophical cell with the road car. It’s a tubular spaceframe wrapped in carbon fiber bodywork loosely resembling an Escudo — in the same way a wolf vaguely resembles a golden retriever when described to someone who has never seen either.

It exists for one purpose: to murder altitude.

Nestled in the middle of the chassis is a 2.5-liter, twin-turbocharged V6 — the H25A on hallucinogens — tuned to produce “over 900 horsepower,” which is motorsport language for “the dyno refused to continue.”

That figure was claimed at altitude, meaning at sea level the engine could probably tow tectonic plates apart.

This wasn’t a gentle, progressive kind of power. This was a “kick you so hard your genetics rearrange” kind of power. Boost arrived like a loan shark at the door — sudden, aggressive, and threatening to break your understanding of traction.

Turbo lag? Yes. Enough lag to make you think the car is contemplating your driving competence. But once the turbos wake up, the Escudo hurls itself forward with the urgency of a man sprinting from a wasp nest.

And the sound.

Good lord.

It isn’t a roar. It’s a shriek — a metallic scream as if the very air is being tortured. At full throttle, it sounds like a dragon being vacuum-cleaned.

The 1998 Escudo’s aero package looks like the result of a corporate meeting where someone said: “What if we just… add more?” and everyone else clapped.

The front wing is wide enough to land drones on. The rear wing is comically large — so huge you would half expect it to generate its own weather system. Then there are the colossal sideboards, the exaggerated wheel arches, and the splitters so sharp you could slice fruit on them.

The design philosophy was simple:

At speed, the Escudo generated downforce in quantities that would make a Formula One car look apologetic. If you printed out every aerodynamic equation used to design it, the stack of paper would reach the summit of Pikes Peak.

The spaceframe chassis was crafted by Monster Sport — Tajima’s empire of mechanical misbehavior — and it was built with the rigidity of military equipment. Welded steel tubes formed a skeleton so stiff that hitting a pothole probably caused the Earth to vibrate, not the car.

.jpg)

The suspension? Custom. Adjustable. Purpose-built to handle surfaces ranging from tarmac to gravel to existential dread.

Brakes the size of a mortgage payment.

Wheels wrapped in tyres so wide they looked like they’d eaten smaller tyres for breakfast.

Everything had one job: survive the mountain.

Picture this. You strap into the Escudo. The belts squeeze your ribs. The engine fires behind you like a small industrial revolution. You roll onto the throttle…

And immediately regret being born.

The car doesn’t accelerate; it pounces. It devours straightaways. Corners become knife-edge moments of commitment. The steering wheel vibrates with the ferocity of an angry spirit. Every bump feels like a punch. Every shift is a slap of violence. Every moment is a negotiation between ambition and the mountain’s desire to kill you.

.jpg)

Monster Tajima handled all of this without blinking. He threw the Escudo into hairpins with the kind of confidence normally associated with people who own parachutes.

Watching him drive it was borderline spiritual — a mixture of fear, awe, and the vague suspicion that he had ascended into a different species.

Pikes Peak sits at 14,115 feet, which is high enough to cause normal humans to pass out while tying their shoes. Air thins. Engines gasp. Brakes smolder. Drivers hallucinate. Your body feels like it’s aging in real time.

Yet the Escudo didn’t merely handle altitude — it weaponized it.

The twin turbos thrived in the thinner air. The power-to-weight ratio became even more obscene. The monstrous aero kept the car glued to the surface even on loose gravel.

Tajima didn’t drive the mountain.

He attacked it.

By the time he finished, the mountain knew his name.

The ’98 Escudo was the peak of mechanical insolence. It represented the wildest moment of Suzuki’s motorsport program — the ultimate union of Japanese engineering and utter disregard for self-preservation.

That year, the Escudo didn’t just compete.

It terrified.

It rewrote expectations.

It became instant myth.

Drivers around the world saw footage and thought, “That is either insane or brilliant.”

It was both.

And then came the moment that cemented the Escudo in global pop culture: Gran Turismo 2.

In the game, the ’98 Escudo Pikes Peak Special wasn’t overpowered.

It was ridiculous.

It accelerated so violently the camera couldn’t keep up. It cornered like a frustrated deity. It made every other car feel like a shopping trolley with hopes and dreams.

For millions, the Escudo wasn’t a race car — it was the final boss of gravity.

.jpeg)

Kids didn’t just remember it.

They worshipped it.

Some never learned where Pikes Peak is, but they knew one thing:

If you need to win anything, choose the Escudo.

Today, the 1998 Escudo Pikes Peak Special is effectively priceless.

You cannot buy one.

You cannot order one.

You cannot even politely ask for one.

Monster Sport guards the remaining cars as if they contain state secrets. Museums drool. Collectors fantasize. Enthusiasts speak of it in the same tone monks reserve for ancient relics.

It is not a classic car.

It is a chapter of motorsport scripture.

In a world where racing is computerized, sanitized, and optimized to please corporate shareholders, the Escudo represents something far more important:

Human insanity.

Actual, glorious, engineering insanity.

It came from a time when motorsport innovation wasn’t afraid to be ugly, dangerous, excessive, and wondrous. When ambition outweighed regulations. When drivers like Tajima could pilot madness without a committee meeting.

It is a monument to audacity — a reminder that sometimes the best machines are the ones built without adult supervision.

Stand on Pikes Peak at dawn and imagine the sound of a twin-turbo V6 echoing off the cliffs — a sound sharp enough to cut the sky. For a moment, you can almost see the ’98 Escudo clawing its way upward, wings slicing mist, turbos shrieking, gravity begging for mercy.

It wasn’t built for roads.

It wasn’t built for comfort.

It wasn’t built for sense.

It was built for one purpose:

To prove that fear is optional when speed is not.

And that’s why the Suzuki V6 Escudo Pikes Peak Special ’98 remains one of the most gloriously unhinged race cars ever created — a myth forged in carbon, fire, and a man brave enough to tame it.