How a Noisy Little Bug Outlived Dictators, Out-sold Detroit, Won Hollywood, and Became the Unlikely Hero of 1968

The Volkswagen Beetle is a car with a résumé stranger than any actor in Hollywood. Think about it: dreamed up under the shadow of Hitler, engineered by Ferdinand Porsche, resurrected from rubble by Ivan Hirst of the British Army, nurtured into global success by Heinz Nordhoff, and finally adopted by Californian surfers who thought soap was optional.

By 1968, the Beetle had transcended its shady birth certificate. It was no longer the “people’s car” of Germany. It was now the people’s car of everywhere. From Mexico City to Manchester, São Paulo to San Francisco, this little bug had become the world’s automotive Esperanto—understood by all, mistranslated by none.

In America, land of chrome V8s, it arrived like a polite German exchange student with odd shoes. But while Detroit shouted about cubic inches and tailfins, Volkswagen whispered: “It’s cheap. It works. You’ll grow to love it.” And America, to its own astonishment, did.

The 1968 Beetle was, on paper, a mechanical contradiction. Its heart was a 1.5-liter, air-cooled flat-four engine that looked like it belonged in a lawnmower, yet it would happily run until the end of civilization. With a monumental 53 horsepower, it wasn’t going to win drag races—but it would start in Siberia after a blizzard or Baja after a sandstorm.

The gearbox? A four-speed manual as honest as a farmer’s handshake. But 1968 also saw the infamous “Autostick.” This was Volkswagen’s attempt to meet the American market halfway, for those terrified of a clutch pedal. It had a torque converter and a semi-automatic clutch that engaged when you touched the gear lever. Brilliant idea in theory, baffling in practice.

Suspension was torsion bar, ride height comically high, body shape unchanged since the war. In other words: while Detroit reinvented cars every two years, Wolfsburg simply tightened the bolts and said, “Nein, this is fine.”

Driving a 1968 Beetle was not like driving a car. It was like piloting an appliance that had accidentally sprouted wheels. Steering was vague, brakes were drum-based prayers, and acceleration required patience, optimism, and a gentle downhill.

Yet, it had charm. You could thrash it mercilessly, and it never truly broke. In snow, the rear-engine layout gave it traction that would embarrass pickup trucks. In rain, it fogged up instantly, forcing owners into contortionist window-wiping exercises. But everyone remembers the same thing: the Beetle made you smile.

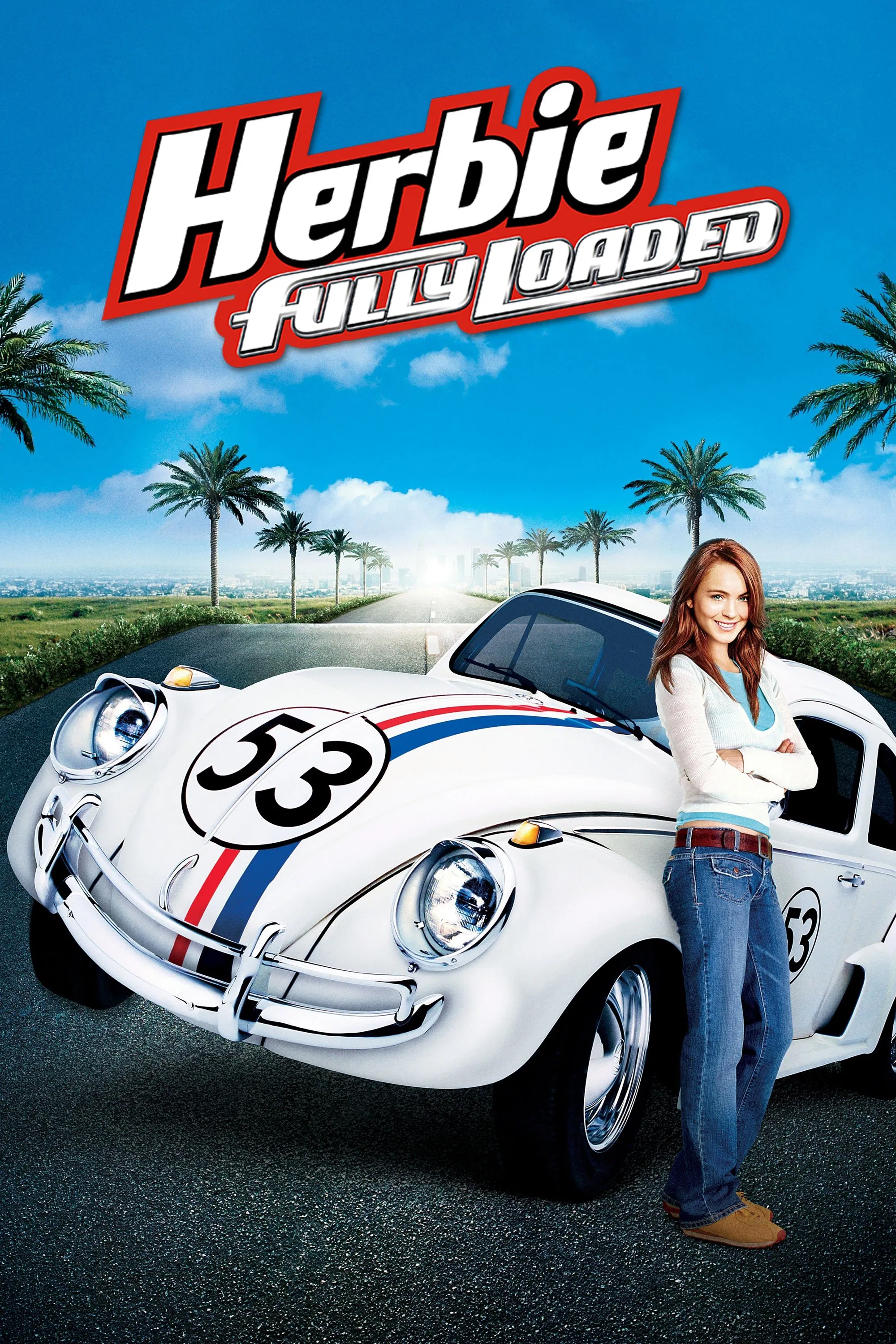

1968 wasn’t just another year for the Beetle; it was the year it became a star. Disney released The Love Bug, and Herbie was born. For many, their first introduction to this car wasn’t mechanical—it was cinematic. A Beetle with eyes, a heart, and more personality than most Hollywood actors.

At the same time, students in Paris, Berlin, and Berkeley were rioting against war, capitalism, and bad haircuts. And what car did they arrive in? Not a Cadillac. Not a Jaguar. A Beetle. Because if you wanted to appear earnest, countercultural, and slightly broke, nothing screamed “I am one of you” louder than a Bug covered in peace stickers.

Musicians, too, couldn’t resist. Janis Joplin painted hers in psychedelic swirls. Paul Newman tinkered with one as a young racer. Even Steve McQueen, the King of Cool, drove one daily because it was the only thing nobody expected him to own.

Although it looked like something you’d find in a toy box, the Beetle had surprising racing pedigree. In America, Formula Vee emerged—an entry-level racing class using Beetle engines, suspension, and gearboxes. It created thousands of amateur racers, some of whom graduated to serious motorsport careers.

Then there were the “Baja Bugs,” Beetles stripped, lifted, and hurled across Mexican deserts. What began as lunacy became legend: the Beetle could survive where pickup trucks failed. The 1968 Beetle was right there at the dawn of this scene, its simple mechanics perfect for field repairs with nothing more than pliers and hope.

Today, collectors drool over early “split window” Beetles from the 1940s or ultra-rare “Oval” window cars of the 1950s. The 1968? It’s a middle child—not the rarest, not the newest. But that’s its magic. It’s affordable, plentiful, and still dripping with chrome. A ’68 is a perfect starter drug for classic car enthusiasts.

The value is climbing, slowly. Restored examples can fetch respectable sums, but part of the Beetle’s appeal is that it still exists in backyards, barns, and student garages. Unlike Ferraris, Beetles were never locked away—they were used, loved, and passed down like eccentric family heirlooms.

So why single out 1968? Because it was the Beetle’s tipping point. It was the year of Herbie. The year of global sales peaking. The year when the world, embroiled in protest, found comfort in a car that was cheap, friendly, and stubbornly unchanged.

In 1968, the Beetle wasn’t just transport. It was identity. If you were a hippie, it was your protest wagon. If you were a suburban dad, it was your second car. If you were Hollywood, it was box-office gold.

By the time production finally ended in 2003 in Mexico, over 21 million Beetles had been built. The 1968 model sits at the very center of that timeline—not the beginning, not the end, but the moment it truly ruled the world.

It wasn’t fast. It wasn’t advanced. It wasn’t luxurious. But it was honest. It proved that design continuity, mechanical simplicity, and a strange sort of cuteness could triumph over horsepower, status, and technology.

The Beetle of 1968 wasn’t just a car. It was a smile on wheels.

-