until innovation wins too hard. And nothing screams “Team Lotus” more than being told, in effect, “Please stop being clever.”

The Lotus Type 88 is the most British kind of genius: the sort that’s obviously clever, slightly cheeky, and guaranteed to annoy a room full of officials with clipboards. It never actually raced in a Grand Prix, yet it’s more famous than many cars that did. Which tells you everything you need to know: in Formula 1, the quickest way to become a legend is either to win Monaco… or to frighten everyone so much they ban you before Sunday.

Here’s the problem Lotus was trying to solve in 1981: ground effect. To make the tunnels under the car really work, you want the floor and skirts held at a stable ride height, which typically means very stiff suspension. Great for aerodynamics. Horrible for the driver, who then experiences the circuit like it’s written in Braille. Lotus’ solution wasn’t to accept the compromise. Lotus’ solution was to separate the compromises.

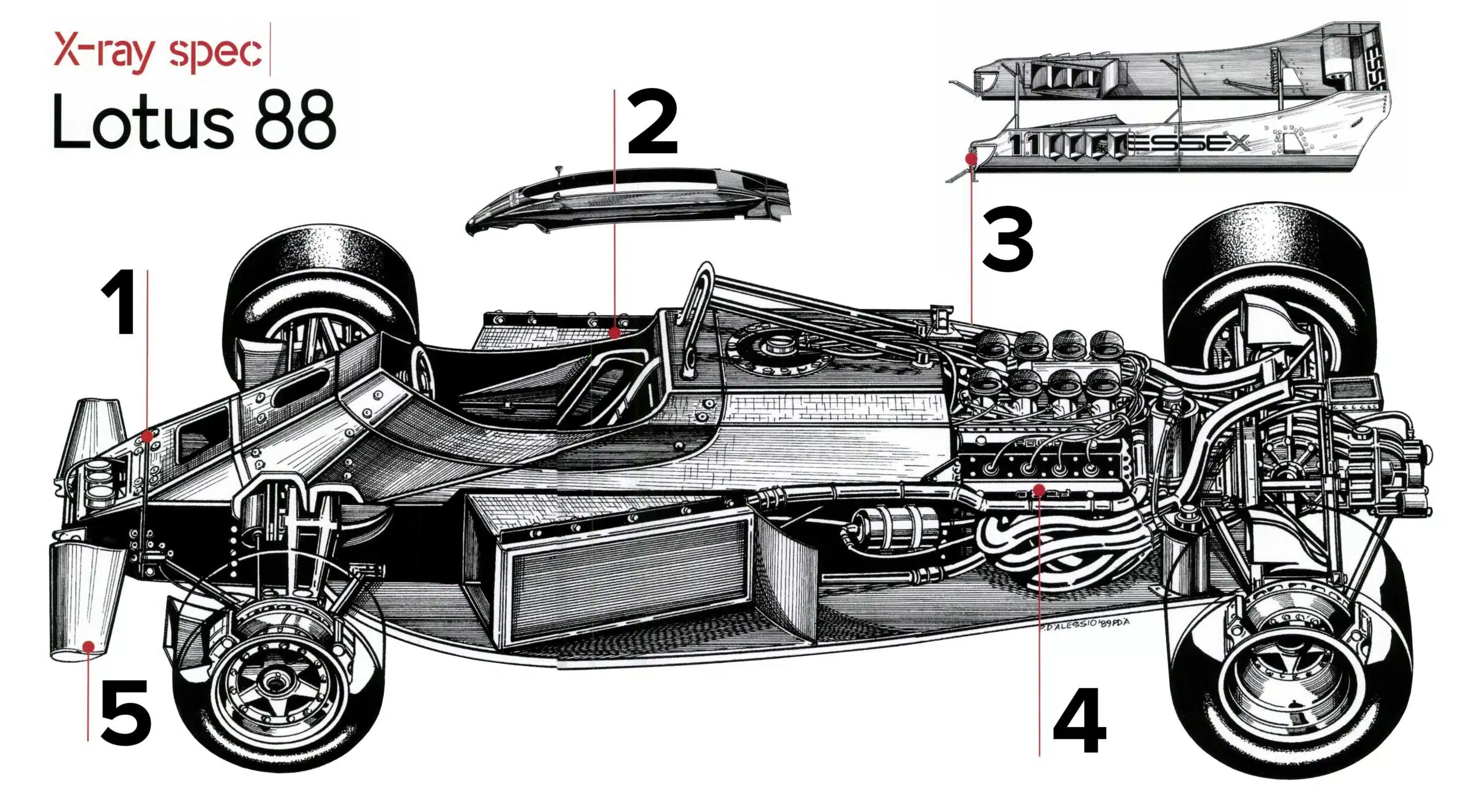

So Chapman’s team built a car with two structures: a “soft” inner chassis for the driver and mechanical bits, and a “stiff” outer structure that carried the aero bodywork and could stay planted at the perfect height. Think of it like this: most teams had one car that had to be both comfortable and aero-perfect. Lotus built two cars occupying the same space, each doing its own job, and told the rulebook, with a straight face, that this was absolutely fine.

Now the numbers, because this is where the Type 88 stops being a clever story and starts being a proper machine. Power came from the classic Ford Cosworth DFV V8, 2,993 cc, naturally aspirated. In Type 88B specification it’s commonly quoted at about 490 bhp (366 kW) at 10,750 rpm, with around 353 Nm at 9,000 rpm. That is a lot of engine for an era when traction control was your right foot and divine mercy.

.jpg)

The gearbox was a Hewland FGA 5-speed manual, sending drive to the rear wheels, because of course it did—this was still the age of heroic oversteer and moustaches.

Then you look at the packaging and realise why Lotus were always terrifying when they got it right. Dimensions for the 88B are listed around 4,260 mm long, 2,172 mm wide, 1,016 mm tall, with a 2,692 mm wheelbase and track roughly 1,727 mm front / 1,626 mm rear. Weight is around 584–585 kg (without the driver in some listings). That’s basically a carbon-fibre dart with a V8 strapped to it.

And yes—carbon fibre. Lotus’ own historical write-up points out that the Type 88 was the first F1 car built with a carbon-fibre chassis, predating McLaren’s famous MP4/1. If you’re keeping score at home, that means Lotus were not only trying to outsmart the rules; they were also quietly dragging the sport into the future.

So why was it banned? The official reasoning evolved into the idea that the outer structure effectively acted like a movable aerodynamic device, because it wasn’t rigidly attached in the “sprung” way the rulemakers wanted. Rival teams protested. Politics escalated. The car got black-flagged in practice, and after repeated arguments and pressure, it never made a race start.

But here’s the delicious irony: the Type 88 became immortal precisely because it didn’t race. Had it been allowed and turned out merely “quite good,” we’d file it under Interesting Lotus Things and move on. Instead it became the forbidden fruit of engineering: the car everyone thinks might have rewritten 1981 if it had been unleashed. It’s a monument to Chapman’s real talent—he didn’t just design fast cars. He designed new questions. And the sport, occasionally, responds by panicking.

So the Lotus Type 88 sits in history as a machine that proved a point without crossing a finishing line: Formula 1 is innovation… until innovation wins too hard. And nothing screams “Team Lotus” more than being told, in effect, “Please stop being clever.”

-

Colin Chapman, British engineer and founder of Lotus.